November 14, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Please read this post here.

By Tom Kollenborn © 2022 Courtesy of the Apache Junction News and Apache Junction Public Library

Monday, November 21, 2016

Monday, November 14, 2016

Aerial Tram on Superstition Mountain

November 7, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

This is a reminder of what can happen when proposing ideas about how to make destination locations an exciting place to attract visitors to an area. During all the speculation associated with how to bring visitors to the desert area known as Apache Junction in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a great many ideas were suggested. The idea of an aerial tram from the “Superstition Ho Hotel” to the Flat Iron peak on Superstition Mountain was one of the more interesting.

This aerial tram idea fired the imaginations of several people who believed the concept was possible because it had been accomplished at many ski resorts in the western part of the United States. The aerial tram proponents were thinking about huge gondolas carrying 20 to 30 passengers running to the top of Flat Iron every 30 minutes.

They also wanted a walkway constructed around the top edge of the Flat Iron (Ship Rock) for spectacular views of Apache Junction and the East Valley. They proposed a large circular rotating glass restaurant to serve evening meals at premium prices.

Many of the early settlers around Apache Junction strongly opposed the idea and immediately went about organizing a petition drive against such a proposal. These same people fought the incorporation of Apache Junction for decades until the city was finally incorporated in November of 1978.

It wasn’t long before Secretary of Interior Steward Udall voiced his opinion as to whether or not an aerial tram project was possible under current wilderness regulations. He strongly opposed the idea of changing the classification of land involved in this proposal.

It was soon learned that the R2 lands were not included in the wilderness area designation. Siphon Draw was also outside the wilderness boundary and located within the R2 lands. This provided an access to the Flat Iron where the tram’s towers could be constructed. This entire proposal began to look feasible when the R2 lands were examined for accessibility. The only major problem was the Flat Iron itself was within the boundaries of the wilderness, and the forest service’s wilderness concept strictly prohibited any such use of wilderness lands.

The supporters of the tramway were trying to form a committee and generate interest for the idea. Stewart Udall and Congressman Morris Udall both opposed the proposal. They were against any encroachment of the wilderness. Then there were proposals to change the “wilderness” status to a “national park” status. This idea found some support in Congress. Udall said a small portion of the land could be possibly changed to a National Park status.

The final result of proposals and counter proposals ended with the donation of 320 acres of land to be used as a national recreation park along the Apache Trail in 1967. Eventually this land (BLM) was turned over to the State of Arizona for the purpose of maintaining a park. In 1977 this land became Lost Dutchman State Park.

Lost Dutchman State Park actually was the congressional settlement in this controversy to build a tramway to the top of the Flat Iron. I do remember the controversy and so do others, but I could not find any newspaper accounts about it except for the transfer of land from the R2 lands to the BLM. Then this land was turned over to the State of Arizona. The State of Arizona can’t sell or transfer the title of these lands that form the Lost Dutchman State Park.

This was Congressman Udall’s compromise involving the lands associated with the concept of the tramway to the Flat Iron. Many people opposed the idea of the Superstition Wilderness Area becoming a National Park and others opposed the entire concept of a wilderness area east of Apache Junction. If there had not been some visionaries in those days who believed that wilderness was more important than development; we would have amusement parks with bright lights on top of Superstition Mountain looking down on Apache Junction today.

The facts, renderings and letters concerning this unpopular proposal still lie somewhere hidden from the eyes of historian and the general public. In my research I found several who remember this proposal and the temporary concern it produced in this community.

Today Apache Junction is unique to any other community in the Salt River Valley with this very popular Superstition Wilderness Area of some 242 square miles immediately east of the community. Over a hundred thousand people visit the wilderness area annually and it popularity grows each year.

This is a reminder of what can happen when proposing ideas about how to make destination locations an exciting place to attract visitors to an area. During all the speculation associated with how to bring visitors to the desert area known as Apache Junction in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a great many ideas were suggested. The idea of an aerial tram from the “Superstition Ho Hotel” to the Flat Iron peak on Superstition Mountain was one of the more interesting.

This aerial tram idea fired the imaginations of several people who believed the concept was possible because it had been accomplished at many ski resorts in the western part of the United States. The aerial tram proponents were thinking about huge gondolas carrying 20 to 30 passengers running to the top of Flat Iron every 30 minutes.

They also wanted a walkway constructed around the top edge of the Flat Iron (Ship Rock) for spectacular views of Apache Junction and the East Valley. They proposed a large circular rotating glass restaurant to serve evening meals at premium prices.

Many of the early settlers around Apache Junction strongly opposed the idea and immediately went about organizing a petition drive against such a proposal. These same people fought the incorporation of Apache Junction for decades until the city was finally incorporated in November of 1978.

It wasn’t long before Secretary of Interior Steward Udall voiced his opinion as to whether or not an aerial tram project was possible under current wilderness regulations. He strongly opposed the idea of changing the classification of land involved in this proposal.

It was soon learned that the R2 lands were not included in the wilderness area designation. Siphon Draw was also outside the wilderness boundary and located within the R2 lands. This provided an access to the Flat Iron where the tram’s towers could be constructed. This entire proposal began to look feasible when the R2 lands were examined for accessibility. The only major problem was the Flat Iron itself was within the boundaries of the wilderness, and the forest service’s wilderness concept strictly prohibited any such use of wilderness lands.

The supporters of the tramway were trying to form a committee and generate interest for the idea. Stewart Udall and Congressman Morris Udall both opposed the proposal. They were against any encroachment of the wilderness. Then there were proposals to change the “wilderness” status to a “national park” status. This idea found some support in Congress. Udall said a small portion of the land could be possibly changed to a National Park status.

The final result of proposals and counter proposals ended with the donation of 320 acres of land to be used as a national recreation park along the Apache Trail in 1967. Eventually this land (BLM) was turned over to the State of Arizona for the purpose of maintaining a park. In 1977 this land became Lost Dutchman State Park.

Lost Dutchman State Park actually was the congressional settlement in this controversy to build a tramway to the top of the Flat Iron. I do remember the controversy and so do others, but I could not find any newspaper accounts about it except for the transfer of land from the R2 lands to the BLM. Then this land was turned over to the State of Arizona. The State of Arizona can’t sell or transfer the title of these lands that form the Lost Dutchman State Park.

This was Congressman Udall’s compromise involving the lands associated with the concept of the tramway to the Flat Iron. Many people opposed the idea of the Superstition Wilderness Area becoming a National Park and others opposed the entire concept of a wilderness area east of Apache Junction. If there had not been some visionaries in those days who believed that wilderness was more important than development; we would have amusement parks with bright lights on top of Superstition Mountain looking down on Apache Junction today.

The facts, renderings and letters concerning this unpopular proposal still lie somewhere hidden from the eyes of historian and the general public. In my research I found several who remember this proposal and the temporary concern it produced in this community.

Today Apache Junction is unique to any other community in the Salt River Valley with this very popular Superstition Wilderness Area of some 242 square miles immediately east of the community. Over a hundred thousand people visit the wilderness area annually and it popularity grows each year.

Monday, November 7, 2016

Truth from Fiction

Most historians accept the story that an old prospector

named Jacob Waltz created one of the most popular legends in American

Southwestern history. Storytellers will tell you he spun yarns and gave clues

to a rich lost gold mine in the Superstition Mountains.

However, historians will claim Waltz was a very quiet and secluded individual preferring his privacy. These clues and stories attributed to Waltz continue to attract men and women from around the world to search for gold. The search for gold in these mountains is pure fantasy to many, however others believe this legendary mine is as real as the precious metal itself.

|

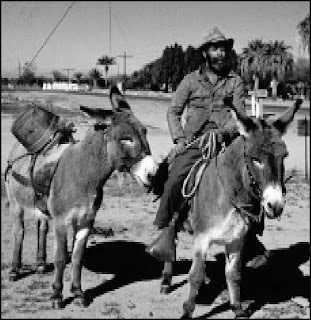

| Prospector ‘Superstition Joe’ (Cecil Vernon) circa 1960, is part of Apache Junction’s legendary past. |

Who was this man who left this lingering story

of lost gold in these mountains? The story of this mine remains the legacy of

this old German prospector.

Jacob Waltz was born somewhere near Oberschwandorf, Wurttenburg, Germany sometime between 1808 and 1810. The exact date and place of his birth is still controversial. The precise date of his birth has not been documented with baptismal records or any other type of documentation. To further confuse the issue here, there was more than one Jacob Waltz born during this period of time.

His childhood was quite obscure because few records remain about his early life in Germany. There are no documents or records that Jacob Waltz had any formal education. There are certainly no records that prove he was a graduated mining engineer as claimed by some writers.

I have a very close friend who lives near Baden-Baden, Germany named Hemut Schmidtpeter. He has researched Jacob Waltz for the past twenty years or so.

The name Jacob Waltz is quite common in Germany and this fact alone confuses research on the topic.

Ironically, some of the most damaging information about Jacob Waltz was passed on to Helen Corbin when she wrote her book titled the “Bible On The Lost Dutchman Mine and Jacob Waltz.”

This information was passed on to her by a researcher named Kraig Roberts. Experts in documentation studied these records and found them to be altered. Did Roberts alter them or somebody else? Nobody knows for sure.

Since the Olbler transit records have been “proved to be altered,” it appears in all probability Waltz may have entered the United States through the port of New York or Baltimore as originally proposed by Jerry Hamrick. The Obler ship passenger’s manifest was definitely altered with the addition of Waltz’s name and others.

Now we can only rely on the existing facts. Waltz did sign his “letter of intent” in Natchez, Mississippi on November 12, 1848, to become a citizen of the United States. Waltz filed for his naturalization papers in Los Angles, California and became a citizen of the United States on July 19, 1861.

He soon traveled to the Bradshaw Mountains near Prescott. Waltz staked three mining claims there between 1863-1868. Waltz also signed a petition for Arizona Territorial Governor Goodwin to form a militia to stop the predatory raid of the local Native Americans on miners and prospectors in the area.

|

| Lost Dutchman Monument on N. Apache Trail. |

Waltz farmed a little and raised a few chickens. He was known for selling eggs in Phoenix. He prospected the mountains around the Salt River Valley.

Did he have a rich gold mine? It is not very likely he did. After his death in 1891 his legacy began to build with the many stories written by newspapermen and authors. Many had a story to tell and didn’t care how they told it.

Fiction replaces fact and we have the story

today that is told around campfires and in cafes around Apache Junction.

Wherever there is a gathering of individuals interested in lost gold mines you

will find the story of the Lost Dutchman mine. This story is still alive and doing well some

one hundred and twenty-five years later.

November 1, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

November 1, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)