December 19, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Read this post here.

By Tom Kollenborn © 2022 Courtesy of the Apache Junction News and Apache Junction Public Library

Monday, December 26, 2016

Monday, December 19, 2016

Unforgettable Christmas

December 12, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Read the Kollenborn Chronicles annual Christmas article here.

Read the Kollenborn Chronicles annual Christmas article here.

Monday, December 5, 2016

Arizona Lecture Series

November 28, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Educators in the Apache Junction Unified School District saw a need for an adult education program to enlighten local residents and winter visitors about Arizona’s history, culture, landmarks, people, and events. The area was experiencing a large growth in new residents and even a larger influx of winter visitors. The task of forming such a program was assigned to Tom Kollenborn, Community School Director, under Superintendent William F. Wright in spring of 1986.

The program was formulated and introduced in a series of six programs called the “Arizona Series” in October of 1986. The first series included six programs. The topics included “This is Arizona,” a geographical review of the state by Tom Kollenborn, “Arizona Archaeology” by Richard Hammon, “Arizona History” by Jim Swanson, “Arizona Fauna and Flora” by Jim Stipes, “Dangerous Animals of the Desert” by Dr. Marc Schmidt, and “Arizona’s Lost Gold” by John D. Wilburn.

The first lecture series required registration and a ten-dollar fee for six lectures about Arizona. The series was originally designed to be a part of the district’s Community Adult Education program.

The community school had targeted a perfect market that was rapidly growing in the Apache Junction area. These new residents were extremely interested in Arizona history, places and events. This soon became a self-supporting program that was capable of funding scholarships and mini-grants to the classroom teachers and students.

The Arizona Lecture Series began in the district boardroom, then moved to the high school band room for more room in 1990. The last year in the band room saw more than 775 patrons attend the Arizona Lecture Series. The program was introduced as an auditorium style series rather than a classroom. The first year in the band room the series attendance averaged around one hundred and forty attendees per program. The series soon outgrew the band room and moved to the new auditorium.

The Apache Junction Unified School District constructed the Performing Arts Center on the high school campus 1990-91. This modern auditorium provided the students, staff and citizens of Apache Junction with an outstanding facility. The Arizona Lecture Series moved into the Performing Arts Center in 1992. Once the series moved into the Performing Arts Center, the character of the series changed as more and more programs were added. The programs begin to focus on specialized areas in Arizona history making the series even more popular with the public.

The new Performing Arts Center could seat six hundred and fifty patrons. The total attendance for the entire series for the first year, 1992, in the auditorium was 3,267. During the years that followed we often had a full house at our lectures.

We contracted our speakers eighteen months ahead so we could develop sufficient advertising for the series. The series has contributed more than hundred thousand dollars to the high school scholarship fund during the past twenty-two years. The series has contributed close to fifty thousand dollars to the mini-grants for classroom teachers in our district. This successful program is dependent on volunteers who serve as ushers, tickets sales, and greeters.

Since 1986, more than 75,000 patrons have attended the Arizona Lecture Series in Apache Junction. Our patrons have strongly supported the series by purchasing 150 to 300 season tickets annually.

I retired from the school district in August 2009 after thirty-five years. Linda Joyner took over the lectures series from 2010-2015. The Arizona Lecture Series continued to be successful during Ms. Joyner’s leadership. She moved to Michigan at the end of the 2016 season. Mr. Zach Lundquest will manage the 2017 Arizona Lecture Series.

Mr. Lundquest has a great season lined up for patrons of the 2017 lecture series. Season tickets are Fifty Dollars or $5.00 per show. Curtain call is 7:00 p.m. at the Apache Junction High School Performing Arts Center on campus at 2525 S. Ironwood Road. For information about the series call 480-982-1110 Ex. 2250. There will be twelve excellent programs this year.

My wife Sharon still faithfully attends the lectures and so do I on occasion. The Arizona Lecture Series and Public Events Series donates most of the money they raise to the scholarship program after expenses were taken out.

The Arizona Lecture Series at the Apache Junction High School is thirty-one year old and I am proud to have been a part of it.

Educators in the Apache Junction Unified School District saw a need for an adult education program to enlighten local residents and winter visitors about Arizona’s history, culture, landmarks, people, and events. The area was experiencing a large growth in new residents and even a larger influx of winter visitors. The task of forming such a program was assigned to Tom Kollenborn, Community School Director, under Superintendent William F. Wright in spring of 1986.

The program was formulated and introduced in a series of six programs called the “Arizona Series” in October of 1986. The first series included six programs. The topics included “This is Arizona,” a geographical review of the state by Tom Kollenborn, “Arizona Archaeology” by Richard Hammon, “Arizona History” by Jim Swanson, “Arizona Fauna and Flora” by Jim Stipes, “Dangerous Animals of the Desert” by Dr. Marc Schmidt, and “Arizona’s Lost Gold” by John D. Wilburn.

The first lecture series required registration and a ten-dollar fee for six lectures about Arizona. The series was originally designed to be a part of the district’s Community Adult Education program.

The community school had targeted a perfect market that was rapidly growing in the Apache Junction area. These new residents were extremely interested in Arizona history, places and events. This soon became a self-supporting program that was capable of funding scholarships and mini-grants to the classroom teachers and students.

The Arizona Lecture Series began in the district boardroom, then moved to the high school band room for more room in 1990. The last year in the band room saw more than 775 patrons attend the Arizona Lecture Series. The program was introduced as an auditorium style series rather than a classroom. The first year in the band room the series attendance averaged around one hundred and forty attendees per program. The series soon outgrew the band room and moved to the new auditorium.

The Apache Junction Unified School District constructed the Performing Arts Center on the high school campus 1990-91. This modern auditorium provided the students, staff and citizens of Apache Junction with an outstanding facility. The Arizona Lecture Series moved into the Performing Arts Center in 1992. Once the series moved into the Performing Arts Center, the character of the series changed as more and more programs were added. The programs begin to focus on specialized areas in Arizona history making the series even more popular with the public.

The new Performing Arts Center could seat six hundred and fifty patrons. The total attendance for the entire series for the first year, 1992, in the auditorium was 3,267. During the years that followed we often had a full house at our lectures.

We contracted our speakers eighteen months ahead so we could develop sufficient advertising for the series. The series has contributed more than hundred thousand dollars to the high school scholarship fund during the past twenty-two years. The series has contributed close to fifty thousand dollars to the mini-grants for classroom teachers in our district. This successful program is dependent on volunteers who serve as ushers, tickets sales, and greeters.

Since 1986, more than 75,000 patrons have attended the Arizona Lecture Series in Apache Junction. Our patrons have strongly supported the series by purchasing 150 to 300 season tickets annually.

I retired from the school district in August 2009 after thirty-five years. Linda Joyner took over the lectures series from 2010-2015. The Arizona Lecture Series continued to be successful during Ms. Joyner’s leadership. She moved to Michigan at the end of the 2016 season. Mr. Zach Lundquest will manage the 2017 Arizona Lecture Series.

Mr. Lundquest has a great season lined up for patrons of the 2017 lecture series. Season tickets are Fifty Dollars or $5.00 per show. Curtain call is 7:00 p.m. at the Apache Junction High School Performing Arts Center on campus at 2525 S. Ironwood Road. For information about the series call 480-982-1110 Ex. 2250. There will be twelve excellent programs this year.

My wife Sharon still faithfully attends the lectures and so do I on occasion. The Arizona Lecture Series and Public Events Series donates most of the money they raise to the scholarship program after expenses were taken out.

The Arizona Lecture Series at the Apache Junction High School is thirty-one year old and I am proud to have been a part of it.

Monday, November 21, 2016

Monday, November 14, 2016

Aerial Tram on Superstition Mountain

November 7, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

This is a reminder of what can happen when proposing ideas about how to make destination locations an exciting place to attract visitors to an area. During all the speculation associated with how to bring visitors to the desert area known as Apache Junction in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a great many ideas were suggested. The idea of an aerial tram from the “Superstition Ho Hotel” to the Flat Iron peak on Superstition Mountain was one of the more interesting.

This aerial tram idea fired the imaginations of several people who believed the concept was possible because it had been accomplished at many ski resorts in the western part of the United States. The aerial tram proponents were thinking about huge gondolas carrying 20 to 30 passengers running to the top of Flat Iron every 30 minutes.

They also wanted a walkway constructed around the top edge of the Flat Iron (Ship Rock) for spectacular views of Apache Junction and the East Valley. They proposed a large circular rotating glass restaurant to serve evening meals at premium prices.

Many of the early settlers around Apache Junction strongly opposed the idea and immediately went about organizing a petition drive against such a proposal. These same people fought the incorporation of Apache Junction for decades until the city was finally incorporated in November of 1978.

It wasn’t long before Secretary of Interior Steward Udall voiced his opinion as to whether or not an aerial tram project was possible under current wilderness regulations. He strongly opposed the idea of changing the classification of land involved in this proposal.

It was soon learned that the R2 lands were not included in the wilderness area designation. Siphon Draw was also outside the wilderness boundary and located within the R2 lands. This provided an access to the Flat Iron where the tram’s towers could be constructed. This entire proposal began to look feasible when the R2 lands were examined for accessibility. The only major problem was the Flat Iron itself was within the boundaries of the wilderness, and the forest service’s wilderness concept strictly prohibited any such use of wilderness lands.

The supporters of the tramway were trying to form a committee and generate interest for the idea. Stewart Udall and Congressman Morris Udall both opposed the proposal. They were against any encroachment of the wilderness. Then there were proposals to change the “wilderness” status to a “national park” status. This idea found some support in Congress. Udall said a small portion of the land could be possibly changed to a National Park status.

The final result of proposals and counter proposals ended with the donation of 320 acres of land to be used as a national recreation park along the Apache Trail in 1967. Eventually this land (BLM) was turned over to the State of Arizona for the purpose of maintaining a park. In 1977 this land became Lost Dutchman State Park.

Lost Dutchman State Park actually was the congressional settlement in this controversy to build a tramway to the top of the Flat Iron. I do remember the controversy and so do others, but I could not find any newspaper accounts about it except for the transfer of land from the R2 lands to the BLM. Then this land was turned over to the State of Arizona. The State of Arizona can’t sell or transfer the title of these lands that form the Lost Dutchman State Park.

This was Congressman Udall’s compromise involving the lands associated with the concept of the tramway to the Flat Iron. Many people opposed the idea of the Superstition Wilderness Area becoming a National Park and others opposed the entire concept of a wilderness area east of Apache Junction. If there had not been some visionaries in those days who believed that wilderness was more important than development; we would have amusement parks with bright lights on top of Superstition Mountain looking down on Apache Junction today.

The facts, renderings and letters concerning this unpopular proposal still lie somewhere hidden from the eyes of historian and the general public. In my research I found several who remember this proposal and the temporary concern it produced in this community.

Today Apache Junction is unique to any other community in the Salt River Valley with this very popular Superstition Wilderness Area of some 242 square miles immediately east of the community. Over a hundred thousand people visit the wilderness area annually and it popularity grows each year.

This is a reminder of what can happen when proposing ideas about how to make destination locations an exciting place to attract visitors to an area. During all the speculation associated with how to bring visitors to the desert area known as Apache Junction in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a great many ideas were suggested. The idea of an aerial tram from the “Superstition Ho Hotel” to the Flat Iron peak on Superstition Mountain was one of the more interesting.

This aerial tram idea fired the imaginations of several people who believed the concept was possible because it had been accomplished at many ski resorts in the western part of the United States. The aerial tram proponents were thinking about huge gondolas carrying 20 to 30 passengers running to the top of Flat Iron every 30 minutes.

They also wanted a walkway constructed around the top edge of the Flat Iron (Ship Rock) for spectacular views of Apache Junction and the East Valley. They proposed a large circular rotating glass restaurant to serve evening meals at premium prices.

Many of the early settlers around Apache Junction strongly opposed the idea and immediately went about organizing a petition drive against such a proposal. These same people fought the incorporation of Apache Junction for decades until the city was finally incorporated in November of 1978.

It wasn’t long before Secretary of Interior Steward Udall voiced his opinion as to whether or not an aerial tram project was possible under current wilderness regulations. He strongly opposed the idea of changing the classification of land involved in this proposal.

It was soon learned that the R2 lands were not included in the wilderness area designation. Siphon Draw was also outside the wilderness boundary and located within the R2 lands. This provided an access to the Flat Iron where the tram’s towers could be constructed. This entire proposal began to look feasible when the R2 lands were examined for accessibility. The only major problem was the Flat Iron itself was within the boundaries of the wilderness, and the forest service’s wilderness concept strictly prohibited any such use of wilderness lands.

The supporters of the tramway were trying to form a committee and generate interest for the idea. Stewart Udall and Congressman Morris Udall both opposed the proposal. They were against any encroachment of the wilderness. Then there were proposals to change the “wilderness” status to a “national park” status. This idea found some support in Congress. Udall said a small portion of the land could be possibly changed to a National Park status.

The final result of proposals and counter proposals ended with the donation of 320 acres of land to be used as a national recreation park along the Apache Trail in 1967. Eventually this land (BLM) was turned over to the State of Arizona for the purpose of maintaining a park. In 1977 this land became Lost Dutchman State Park.

Lost Dutchman State Park actually was the congressional settlement in this controversy to build a tramway to the top of the Flat Iron. I do remember the controversy and so do others, but I could not find any newspaper accounts about it except for the transfer of land from the R2 lands to the BLM. Then this land was turned over to the State of Arizona. The State of Arizona can’t sell or transfer the title of these lands that form the Lost Dutchman State Park.

This was Congressman Udall’s compromise involving the lands associated with the concept of the tramway to the Flat Iron. Many people opposed the idea of the Superstition Wilderness Area becoming a National Park and others opposed the entire concept of a wilderness area east of Apache Junction. If there had not been some visionaries in those days who believed that wilderness was more important than development; we would have amusement parks with bright lights on top of Superstition Mountain looking down on Apache Junction today.

The facts, renderings and letters concerning this unpopular proposal still lie somewhere hidden from the eyes of historian and the general public. In my research I found several who remember this proposal and the temporary concern it produced in this community.

Today Apache Junction is unique to any other community in the Salt River Valley with this very popular Superstition Wilderness Area of some 242 square miles immediately east of the community. Over a hundred thousand people visit the wilderness area annually and it popularity grows each year.

Monday, November 7, 2016

Truth from Fiction

Most historians accept the story that an old prospector

named Jacob Waltz created one of the most popular legends in American

Southwestern history. Storytellers will tell you he spun yarns and gave clues

to a rich lost gold mine in the Superstition Mountains.

However, historians will claim Waltz was a very quiet and secluded individual preferring his privacy. These clues and stories attributed to Waltz continue to attract men and women from around the world to search for gold. The search for gold in these mountains is pure fantasy to many, however others believe this legendary mine is as real as the precious metal itself.

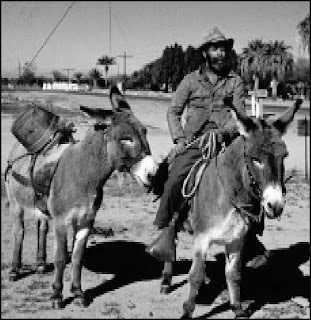

|

| Prospector ‘Superstition Joe’ (Cecil Vernon) circa 1960, is part of Apache Junction’s legendary past. |

Who was this man who left this lingering story

of lost gold in these mountains? The story of this mine remains the legacy of

this old German prospector.

Jacob Waltz was born somewhere near Oberschwandorf, Wurttenburg, Germany sometime between 1808 and 1810. The exact date and place of his birth is still controversial. The precise date of his birth has not been documented with baptismal records or any other type of documentation. To further confuse the issue here, there was more than one Jacob Waltz born during this period of time.

His childhood was quite obscure because few records remain about his early life in Germany. There are no documents or records that Jacob Waltz had any formal education. There are certainly no records that prove he was a graduated mining engineer as claimed by some writers.

I have a very close friend who lives near Baden-Baden, Germany named Hemut Schmidtpeter. He has researched Jacob Waltz for the past twenty years or so.

The name Jacob Waltz is quite common in Germany and this fact alone confuses research on the topic.

Ironically, some of the most damaging information about Jacob Waltz was passed on to Helen Corbin when she wrote her book titled the “Bible On The Lost Dutchman Mine and Jacob Waltz.”

This information was passed on to her by a researcher named Kraig Roberts. Experts in documentation studied these records and found them to be altered. Did Roberts alter them or somebody else? Nobody knows for sure.

Since the Olbler transit records have been “proved to be altered,” it appears in all probability Waltz may have entered the United States through the port of New York or Baltimore as originally proposed by Jerry Hamrick. The Obler ship passenger’s manifest was definitely altered with the addition of Waltz’s name and others.

Now we can only rely on the existing facts. Waltz did sign his “letter of intent” in Natchez, Mississippi on November 12, 1848, to become a citizen of the United States. Waltz filed for his naturalization papers in Los Angles, California and became a citizen of the United States on July 19, 1861.

He soon traveled to the Bradshaw Mountains near Prescott. Waltz staked three mining claims there between 1863-1868. Waltz also signed a petition for Arizona Territorial Governor Goodwin to form a militia to stop the predatory raid of the local Native Americans on miners and prospectors in the area.

|

| Lost Dutchman Monument on N. Apache Trail. |

Waltz farmed a little and raised a few chickens. He was known for selling eggs in Phoenix. He prospected the mountains around the Salt River Valley.

Did he have a rich gold mine? It is not very likely he did. After his death in 1891 his legacy began to build with the many stories written by newspapermen and authors. Many had a story to tell and didn’t care how they told it.

Fiction replaces fact and we have the story

today that is told around campfires and in cafes around Apache Junction.

Wherever there is a gathering of individuals interested in lost gold mines you

will find the story of the Lost Dutchman mine. This story is still alive and doing well some

one hundred and twenty-five years later.

November 1, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

November 1, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Monday, October 31, 2016

Civil War in the Superstitions

October 24, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Several years ago I heard a couple talking about witnessing an American Civil War skirmish in the Superstition Wilderness between the Union and Confederate soldiers. As I listened, it sounded quite bizarre. The couple said they were hiking between Peralta Trail Head and First Water Trail Head when they came across two Civil War military detachments near Brush Corral. Members of the detachment didn’t speak or look at them. Actually the soldiers were like ghostly images in military uniforms. Some of the men were mounted cavalry and others were marching infantry.

Several years ago I heard a couple talking about witnessing an American Civil War skirmish in the Superstition Wilderness between the Union and Confederate soldiers. As I listened, it sounded quite bizarre. The couple said they were hiking between Peralta Trail Head and First Water Trail Head when they came across two Civil War military detachments near Brush Corral. Members of the detachment didn’t speak or look at them. Actually the soldiers were like ghostly images in military uniforms. Some of the men were mounted cavalry and others were marching infantry.

Their story fired my curiosity. I started to

investigate their story. They assured me they were not telling a tall tale, yet

I couldn’t find any account of a civil war military action in the Superstition

Mountain area that would have justified a re-enactment.

The next thing was to try and contact some of the local Civil War re-enactment groups for information. I was absolutely certain there were no Civil War battles in the Superstition Wilderness Area and the nearest skirmish was fought at Picacho Peak in April of 1864. I did find some information about a skirmish fought near Pinyon Camp in the Superstition in 1866 by the Arizona 1st Volunteers led by Brevet Lt. John D. Walker against the Apaches. This battle was fought after the Civil War ended. As I continued my research a story began to emerge.

Yes, a civil war skirmish had occurred in the Superstition Wilderness. Actually there were two skirmishes— one at Pinyon Camp along the Peralta Trail FS 102 and one at Brush Corral in Boulder Basin between West Boulder and East Boulder Canyons. The engagement at Brush Corral was between two cavalry units and two infantry units. The skirmish at Pinyon Canyon was between an infantry company and a cavalry unit.

An infantry company had ambushed the cavalry unit at Pinyon Camp. Re-enactment groups from Phoenix, Tucson and Mesa recreated these skirmishes on November 14, 1984. The circumstances and details of these skirmishes are now available after some thirty years. Several groups made these re-enactment skirmishes possible. These units were from the 7th Confederate States Cavalry, Mesa, Arizona, the 6th U.S. Cavalry, Tucson, Arizona, the 7th Georgia Infantry Regiment and the 1st U.S. Infantry, both units from Phoenix, Arizona.

The infantry units entered the mountains from First Water Trail Head and Peralta Trail Head at 7 a.m. on November 14, 1984, and the cavalry units entered the mountains from First Water and Peralta Trail Heads at 8 a.m. An ambush was staged at Pinyon Camp between an infantry unit and a cavalry unit. All units met at Brush Corral for the battle between Union and Confederate forces in the Superstitions.

The 7th Confederate Cavalry Re-enactment group organized the annual Picacho State Park re-enactment of the only American Civil War battle in Arizona. Several thousand people drove to Picacho State Park each year between 1979-2016 on the second weekend in March to witness the outstanding portrayal of the “War Between The States” skirmish in Arizona. Larry Hedrick of Apache Junction headed this group and did all the announcing between 1979-1992.

The 7th Confederate Cavalry also participated in the Inaugural Parade for Ronald Reagan on January 20, 1985. They also served as the Honor Guard at the Capitol Rotunda during the Inaugural Event and marched in the Inaugural Parade for George H. W. Bush. The group also recreated the Battle of Gettysburg at Apache Land on July 3 and 4, 1979 for Arizona to witness. The battle drew several hundred people.

An old friend of mine, Dan Hopper, was at Parker Pass on the Dutchman Trail when he witnessed an infantry unit pass him and his partner. He said they were all in uniform carrying what appeared to be cap and ball rifles of the Civil War period. He said none of the soldiers talked or look at them. He also said they were like ghostly figures marching into battle. Dan just recently told me this story. If you were a witness to this re-enactment in the Superstition Wilderness Area in 1984, you now know the whole story.

|

| Larry Hedrick, organizer of the 7th Confederate Cavalry Reenactment group and central in the founding of the Superstition Mountain Museum. Photo by the Arizona Republic. |

The legendary 7th Confederate Cavalry Unit has been

disbanded for several years. Lt. Larry Hedrick organized and commanded this

unit. The unit was cited many times for community service and historical

preservation in Arizona. Hedrick was dedicated to preserving the history of the

Picacho Pass, Arizona’s only American Civil War battle. A lot of history was

associated with this skirmish in the Arizona desert near Piacacho Peak, which

today is known as Piacacho State Park along I-10 Highway between Phoenix and

Tucson.

Larry Hedrick also dedicated more than thirty-five

years to the concept and building of a museum devoted to the preservation of

the history and lore of Superstition Mountain and the Lost Dutchman Mine. I

worked closely with Larry during the first ten years and witnessed his dedication,

devotion and hard work to see the concept materialize into its building at

Goldfield Ghost Town on January 31, 1990. Finally the museum had a building.

This required ten years of hard work and dedication to a cause. I am certain it

would have never happened without Larry Hedrick working closely with Bob

Schoose to make this dream come true. We all stood proudly in front of the new

museum building on January 31, 1990.

Again, it was Larry Hedrick who pursued the land transfers that eventually led to the money and property the museum board eventually acquired. This story is a reminder of just what goes into a dream and an idea that it is designed to protect and preserve the history of any given area or event.

History begins with proper preservation. The

future lies in the hands of historians and those who guard the events of our

times for the future. Larry R. Hedrick was such a man. He is a man who should

be recognized for his dedication, determination and devotion to history and

this museum. There needs to be something better than just a plaque. Something

heroic needs to recall this man’s dedication, determination, devotion, and work

in this community.

Monday, October 24, 2016

Murder Conspiracy At The U Ranch

October 17, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Recently I read on the internet about a local cattle family’s ranch being used to hatch a murder conspiracy. The murder conspiracy supposedly included Abe Reid, George “Brownie” Holmes, Milton Rose, Jack Keenan and Leroy Purnell. The ranch was the Quarter Circle U in Pinal County and the man to be murdered was Adolph Ruth, a Washington D.C. gold prospector. The year was 1931.

Recently I read on the internet about a local cattle family’s ranch being used to hatch a murder conspiracy. The murder conspiracy supposedly included Abe Reid, George “Brownie” Holmes, Milton Rose, Jack Keenan and Leroy Purnell. The ranch was the Quarter Circle U in Pinal County and the man to be murdered was Adolph Ruth, a Washington D.C. gold prospector. The year was 1931.

The story goes something like this. Dr. Adolph Ruth arrived in Arizona in mid-May of 1931. He was searching for a pointed peak in the Superstition Mountains based on a map his son acquired in Mexico in 1914, which he believed would lead him to buried gold in the Superstitions. The old man was convinced he would be successful in these mountains because he had failed in California.

Ruth had searched in the southern California desert previously with another map he had acquired from his son. This trip was in December of 1919. Ruth was severely injured during this experience and almost lost his life. His limited success in the Anza-Borrego Desert of California convinced Ruth he would have better success in Arizona.

Ruth arrived in Arizona in May 1931 and went about trying to find somebody to take him into the Superstition Mountains. He eventually ended up at the old Bark Ranch or what Barkley called the Quarter Circle U Ranch. It was there he met William Augustus “Gus” Barkley.

|

| Dr. Adolph Ruth was last seen on the morning on June 18, 1931, by a man he met near the old brush corral south of West Boulder Canyon. |

On June 11, 1931, Ruth tried to persuade Barkley to

take him into the region around Weaver’s Needle. Barkley refused because of

Ruth’s physical condition and the summer heat. Barkley made every effort to

point out the hazards of going into the mountains this time of the year. But

Ruth was a man that could not be discouraged easily after his previous

adventure in the Anza-Borrego Desert near Warner Hot Springs in 1919. Finally,

Barkley agreed to pack Ruth into the mountains but told Ruth to wait three days

for Barkley’s return from a trip to Phoenix.

Barkley left the ranch on June 12, 1931, and returned three days later to find Ruth had already departed for the mountains. Ruth had become impatient during Barkley’s absence and asked two local cowboy-prospectors to pack him into the mountains. These two men were Jack Keenan and Leroy Purnell.

Ruth was packed into the mountains through First Water to a site near Willow Springs in West Boulder Canyon. His campsite was just west of Weaver’s Needle. Ruth’s camp was comfortable, he had water and the temperatures were only up around 94 degrees at midday. Considering the time of the year these temperatures were very moderate.

When Barkley returned to the Quarter Circle U Ranch he found the elderly Ruth had been packed into the mountains. Barkley rode into Ruth’s camp at Willow Springs in West Boulder Canyon on June 20, 1931. After examining the camp he determined Ruth had not used the site for at least twenty-four hours. When Barkley realized the old man was missing he immediately notified the authorities.

A search was mounted and it continued for forty-five days without a trace of Adolph Ruth being found. The search conditions for Ruth were terrible with temperatures reaching the 115-degree mark and the search was finally abandoned around the first of August 1931.

It was later reported that early on the morning on June 18, 1931, Ruth had met a man near the old brush corral south of West Boulder Canyon. This man claimed Ruth was in good shape when he saw him but walked with a limp and appeared a little exhausted. They talked about the weather and the black gnats. Ruth asked the man for directions to Needle Canyon. The man told him how to find the trail over Black Top Mesa Pass and into Needle Canyon. He also noted Ruth was carrying a small side pack, like a military gasbag, and a thermos jug. The man also noted Ruth was carrying a side arm of some kind. This fateful meeting was recorded in the man’s prospecting journal.

This individual never stepped forward during the investigation because by the time he heard about Ruth missing, the search had turned into a murder investigation. It is my contention this was the last human to ever see Adolph Ruth alive. He reported Ruth in good condition, although he thought he was unprepared for such rugged country at this time of the year. When Ruth told him he had a base camp the man wasn’t as concerned.

Ruth’s skull was discovered a few months later on December 10, 1931, by the Phoenix Archaeological Commission’s expedition. Richie Lewis and “Brownie” Holmes led this group. William A. Barkley and Jeff Adams found the skeletal remains of Ruth on the eastern slope of Black Top Mesa on January 8, 1932, about a quarter of a mile from the location of the skull.

There was no final agreement as to exactly how Ruth died, but there was a consensus that he died of natural causes and did not die from some foul deed perpetrated by some evil contriving individual. The periodicals of the period conjured up all kinds of murder and conspiracy theories. These stories were the source of the many tales that survive today. Ruth’s son, Erwin, was convinced his father was murdered for an old Spanish treasure map he possessed. Erwin Ruth was a very melodramatic individual.

It is pure fantasy to believe a person or parties known or unknown conspired at the Quarter Circle U Ranch in 1931 to murder Adolph Ruth for a treasure map he carried. If the cause of Ruth’s death was not murder then there could have been no conspiracy at the U Ranch. Again, all evidence suggests Ruth died of natural causes. Doubt was only raised when Ruth’s son, Erwin, made claims his father was murdered for a map he carried.

This conspiracy story was dreamed up to malign a lot of honest Arizona pioneers because of conflicting beliefs and interest involving lost gold and treasure in the Superstition Wilderness. The Arizona Republic printed the map found on Ruth’s body. One of these individuals was Quentin T. Cox. He had a very fiery pen and often attacked people and their ideas in writing.

Hundreds of his letters exist today and these letters continue to keep this murder conspiracy going. Milton Rose, according to Cox, was one of the conspirators in the Ruth case. Rose also had a fiery pen and countered any story that implied Ruth was murdered.

I met Quentin Cox on several occasions while employed on the Quarter Circle U Ranch in the 1950’s. He often came up to the old U Ranch and visited. His tongue was as fiery as his pen when it came to talking about certain people associated with the Lost Dutchman Mine. I would listen to his rhetoric then go about my chores. Quentin Cox had some interesting stories and he adjusted them according to his theories. It is people like Quentin Cox, Milton Rose and others who keep the tales of the Superstition Wilderness alive and going today.

The Barkleys were true Arizona pioneers who worked

hard to eke a living out of this desert and the Superstition Mountains. The

Barkley’s never felt guilty or haunted about the Ruth incident or anything to

do with it. Old Gus had made every effort to find Adolph Ruth and help his

family. No such murder conspiracy ever occurred at the Quarter Circle U Ranch.

However, each decade the story changes and some people claim other preposterous

statements about the incident that occurred eighty-five years ago.

Monday, October 17, 2016

Feud at Cottonwood Springs

October 10, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

There are those who believe there is an unlimited supply of water. But in the 1890s prospectors, miners and cattlemen fought over small seeps and springs in the desert around Superstition Mountain. The Cottonwood Springs water feud was between a cattleman and a stable owner in the Goldfield mining camp around 1894. The story goes something like this.

There are those who believe there is an unlimited supply of water. But in the 1890s prospectors, miners and cattlemen fought over small seeps and springs in the desert around Superstition Mountain. The Cottonwood Springs water feud was between a cattleman and a stable owner in the Goldfield mining camp around 1894. The story goes something like this.

When the first Mormon gold miners arrived here from Mesa City in 1881 there wasn’t much water in the area. There were no deep wells like we have today. The legendary sources of water in those days were Willow Springs, Cottonwood Springs and a bi-annual seep known as “First Water.”

The alternative sources for water in those days was a eleven-mile trip to Bagley Flat and the Salt River or packing water from Mesa City— a twenty mile journey. Finding water in the early days at the Goldfield Camp was no easy task and the water came at a premium. When the road was built during the early 1890’s water was then hauled to the camp from Mesa City.

The Weeks family had a spring near their place south of the Goldfield Camp and provided water at ten cents a span. That meant it cost ten cents for two horses to have a drive of water. Water was a premium in the area and all sources of water had been claimed at that point.

The cattlemen in the surrounding hills had water sources for their cattle. Sid Lamb had a windmill and a well at Willow Springs and eventually developed the seep or spring at Cottonwood Spring.

John Richards who owned a corral in Goldfield City in 1894, decided he would haul water from Willow and Cottonwood Springs for his corral. This water was much closer than Mesa City or the Salt River, but it wasn’t long before some real problems began to arise.

Sid Lamb wanted to prevent Richards from hauling water from his spring because of the limited supply of water the springs produced. Lamb Brothers had cattle on the range they had to protect and supply with water. Lamb and his brothers filed mill rights on both of the springs in an attempt to prevent Richards from using the water. Water was scarce and expensive in the early 1890s and led to a feud between Lamb and Richards.

Lamb found John Richards at another one of his springs. It was at Cottonwood Springs and there was a confrontation between the two men. Richards was cleaning out the spring when Sid Lamb and Walter Rogers rode up on him.

Lamb told Richards to leave the spring alone. He said the water was for his cattle and ordered him to get out. After an exchange of words, Richards invited Lamb and Rogers to get off their horses. Lamb and Rogers complied with Richard’s request. Lamb attempted to draw his gun, but Richards was faster. Lamb thought discretion in this case was the better part of valor and didn’t shoot. Lamb and Rogers remounted to ride off but Richards threw a rock knocking Lamb off his horse. Lamb got back on his horse and left. He and Rogers filed a complaint against John Richards with the Sheriff of Pinal County and Richards was arrested.

The Lamb Brothers claimed the active or permanent springs in the area for stock water. They had been ranching in this area since the 1880s.

This disagreement continued for a couple of years before an abundant supple of water was located in the Mammoth Mine. When they began pumping water, Goldfield Camp had all the water they needed and the feud ended.

Water is absolute essential for survival on the desert. However, most people take it for granted.

|

| As Tom Kollenborn snaps this photo of Cottonwood Spring his dog cools off in the concrete tank that was added later. |

Monday, October 10, 2016

Dismal Valley

October 3, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Several years ago Joe Clary introduced me to the military records of the Rancheria Campaign in the Superstition Mountain area. It was among these field reports and maps that several new names for various landmarks within the Superstition Wilderness Area were discovered. The Rancheria Campaign against the Apache and Yavapai between the years 1864-1868 eventually ended much of the hostilities along the Gila and Salt Rivers.

Several years ago Joe Clary introduced me to the military records of the Rancheria Campaign in the Superstition Mountain area. It was among these field reports and maps that several new names for various landmarks within the Superstition Wilderness Area were discovered. The Rancheria Campaign against the Apache and Yavapai between the years 1864-1868 eventually ended much of the hostilities along the Gila and Salt Rivers.

The region east of Tortilla Creek and west of

Fish Creek Canyon formed a small alluvial flat that was once the site of the

Tortilla Ranch. Cattlemen and cowboys have used this valley for stock

gathering and raising for more than a hundred years.

Prior to the cattlemen’s use of this valley, it was an important Native American encampment or farmstead. During the 1860s the Apaches and Yavapais had a rancheria in the valley. This village was used on an intermittent basis because of the water supply. When water was abundant the Native Americans grew maize, beans and squash along Tortilla Creek.

The Apaches and Yavapais had a nasty habit of raiding their distant neighbors along the Salt and Gila River for women and additional supplies. Prior to 1860 there was very little the Pimas could do to prevent these raids. It was certain death to challenge the Apache in their mountain sanctuary to the east. The Pimas avoided these mountains because the region was the home of their dreaded enemy.

|

| John D. Walker organized a militia unit of Pimas and white settlers to combat the Apache and Yavapai. This militia was called the 1st Arizona Volunteers. |

Walker’s first campaign against the Apache-Yavapai consisted

of several attacks by his poorly armed and fed group of volunteers. Even

under such conditions this rag-tag militia struck hard against the

Apache-Yavapai rancherias in the Pinal Mountains. The first campaign

consisted of approximately 200 Pima scouts and forty American settlers. Camp McDowell was established along the Verde

River in 1864 to control the predatory raids of the Apache-Yavapai from Tonto

Basin down the Rio Salinas (Salt River) into the Salt River Valley. Units from

the 14th, 24th and 32nd Infantries under the command of Brevet Colonel Bennett

went into the field in 1866 and continued operations until the end of

1868. Their mission was to eliminate hostile villages in the Tonto Basin

area, the Pinal Mountains and the Superstition Mountains.

May 11, 1866, Brevet Lt. John D. Walker led elements

of the 14th and 24th infantries against Apaches and Yavapais in what is known

as the Superstition Wilderness today. Their mission was to destroy all Native

American villages or rancherias and capture or kill all inhabitants they could

find south of the Salt River, north of the Gila River and east of the

Superstition Mountain.

Walker turned southward from the Salt River at a place called Mormon Flat and then followed Tortilla Creek into the mountains. His column first attacked a large encampment of Native Americans above Hell’s Hole on Tortilla Creek. The infantry unit killed 15 warriors at Hell’s Hole. The unit then moved up Tortilla Creek to Dismal Valley. Walker’s command attacked a large Rancheria in Dismal Valley killing fifty-seven Native Americans including several women and children. During the mopping up operation the mosquitoes were so fierce, the stench of the dead was so nauseating and the heat was so extreme the site became known as Dismal Valley.

Walker led several other campaigns into the Superstition Mountain area during the period 1860 to 1868. It was this involvement that led to his name being prominently attached to the story of the Dutchman’s Lost Mine.

Some storytellers believed Walker received a map from Jacob Waltz’s partner, Jacob Wisner. It was believed this map was given to Walker because of his knowledge of the Superstition Wilderness Area. Walker eventually passed this map on to Thomas Weedin, the editor of the Florence Blade.

Joseph Clary’s work with military records in Washington D.C. opened another interesting era in the history of the Superstition Wilderness Area. His research located many new names for landmarks in the area around Tortilla Mountain and in Dismal Valley.

Prospectors and treasure hunters have always linked John D. Walker with Jacob Waltz and his alleged partner Jacob Wisner (Weiser). It is apparent the most logical site for this link was during the military campaign of 1864-1868. The irony of this is the fact Waltz was not in the area until at least 1868. These skirmishes had already been fought. It is highly unlikely Walker came across Waltz or Wisner in the Superstition Mountain area. It is very interesting how facts get mixed with supposition and faith. Walker was not involved with the second campaign against Apaches in the Superstition Mountain region. Major Brown led units of the 5th and 10th United States Cavalries against the Apache in this campaign of the 1870’s.

The Walker-Waltz connection is strictly supposition and there is little or no documentation to support it. It is just another tale about the legendary mountain range east of Apache Junction.

Monday, October 3, 2016

Dutch Hunter’s Rendezvous

September 26, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

The intense interest in the Dutchman’s Lost Mine and the Superstition Mountain continues to this day. Men and women from around our nation come to Arizona hoping to find their fortunes. Most find nothing or loose their fortunes and others are lucky to get away with their very lives. Sadly, some make poor choices and death or injury is no stranger to the unprepared and inexperienced in this rugged mountain range east of Apache Junction.

The intense interest in the Dutchman’s Lost Mine and the Superstition Mountain continues to this day. Men and women from around our nation come to Arizona hoping to find their fortunes. Most find nothing or loose their fortunes and others are lucky to get away with their very lives. Sadly, some make poor choices and death or injury is no stranger to the unprepared and inexperienced in this rugged mountain range east of Apache Junction.

Prospectors have died from extreme weather

conditions, from gunshot wounds, from falls, drowned in flash floods, and from

natural causes. Ironically the rugged Superstition Mountains are far safer than

the streets of Phoenix or the highways of Arizona. Since the early 1880s men and women have

searched these rugged mountains for gold and lost mines. The most significant

lost mine stories centers around an old German immigrant name Jacob Waltz. His

mine was allegedly located near a prominent landmark called Weaver’s Needle

just east of Superstition Mountain.

Maintaining a camp in these mountains can be

difficult at best. The trails are rough and steep, making it difficult to

deliver supplies. Also pack trains (horses or mules) are a very expensive

method in which to move needed items into the wilderness. Furthermore, all

camps are limited to fifteen days by forest service regulations. Camps cannot

be established within a quarter-of-a-mile of a water source. This can

make camping very difficult in the dry season when water is scarce.

|

| Interest in tales of gold and lost mines still fascinate prospectors in the 21st Century. |

One can easily get disoriented in these

mountains if they don’t have map reading experience. No one is immune to the

dangers that exist in these mountains, however caution and common sense will

protect most from serious injury or death. Each year I am amazed at the people who become involved

in the search for the Lost Dutchman Mine. There is a continuous list of new

prospectors who are searching the mountains for clues.

Many years ago a businessman and prospector

named Joe Ribaudo, who lives in Lake Havasu City, decided he wanted to see the

Dutchman legend carried on by some kind of annual gathering. He came up with

the idea of the “Dutch Hunter’s Rendezvous.” He held the first gathering just

west of Twin Buttes and south of the Coke Ovens along the Gila River east of

Florence. The first gathering was small with thirteen attending in October of

2005, however there was a lot of enthusiasm for the idea. The next year, the

rendezvous was moved to Don’s Camp. This was accomplished with the help of

Don’s member Greg Davis.

The camp is located at the base of Superstition Mountain near the Peralta Trailhead. Each year the activity is held at the end of October. The gathering has grown. It is a gathering of individuals that are extremely interested in the Superstition Mountains and its many tales and stories. This event has attracted old timers as well as contemporaries anxious to learn the stories of Superstition Mountain.

The third year, Joe handed over the organizing

of the “Dutchman’s Rendezvous” to Wayne Tuttle and Randy Wright. Greg Davis

continued to make the arrangements for the Don’s Camp for the rendezvous. Joe

and his wife, Carolyn, retired as camp hosts. They will still greet you and say

hello.

The scheduled activities include a variety of options. Friday night includes sitting around a campfire and entertaining each other by telling stories about the mountains. There is usually a guided hike on Saturday. After dark on Saturday, everyone gathers around the large Ramada to listen to a couple of guest speakers. This gathering at the Ramada is also planned for Friday evening. I have attended for last three years and I think it was an excellent opportunity to meet a variety of people from all over the United States that were interested in our history. As I look back I should have made an effort to attend and report on all of these events. Please don’t get this event confused with Lost Dutchman Days in Apache Junction. This has nothing to do with this particular event or the Apache Junction Chamber of Commerce. Last year there were three days of this event. The interested, the curious and the very serious showed up for the event last year. Some of the individuals drove from Texas, California, Oklahoma, New York, New Hampshire, and several other distant locations. The organizers should be proud of their accomplishment. I didn’t personally count each and everyone in attendance, but I would estimate there were about eighty to a hundred people attended last year’s “Dutchman’s Rendezvous” at Don’s Camp.

A number of old time Dutch Hunters attend, and

of course they are legends in their own right. Many authors, who have published

books about the Superstition Mountains and the Lost Dutchman’s mine attend.

I am not sure who are the guest speakers this year, however I am sure they will

be interesting. Wayne made a big improvement last year by adding a sound

system.

The Dutch Hunter’s (Dutchman’s) Rendezvous is an open

event, so everyone is welcome. This year’s event is scheduled for October 21,

22 and 23, 2016. There will be guest speakers on Friday and Saturday night at

the campfire gathering.

The camp is primitive, so you need to bring what you need to be comfortable. Be sure to bring water, food, and bedding if you are spending the night. For more information you may email Joe at havasho@frontiernet.net

Monday, September 26, 2016

Barry Storm

|

| Author and prospector Barry Storm. |

September 19, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Barry Storm was born John Griffith Climenson in Seattle, Washington, on June 4, 1910. He was the son of Sila Griffith and Clara Virginia (Brown) Climenson.

Barry Storm was born John Griffith Climenson in Seattle, Washington, on June 4, 1910. He was the son of Sila Griffith and Clara Virginia (Brown) Climenson.

Storm graduated from high school in Seattle and

became interested in mining, prospecting and writing. He prospected in

California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.

Storm turned to prospecting and treasure hunting

during the “depression” (1930s) shortly after getting out of high school. There

were no jobs, he often said.

Early in 1934, Barry started writing short adventure stories for various pulp magazines such as Home and Office. He also provided numerous articles for various treasure magazines.

Early in 1934, Barry started writing short adventure stories for various pulp magazines such as Home and Office. He also provided numerous articles for various treasure magazines.

Storm arrived in Phoenix in the fall of 1937 with plans to search for the Peralta Mines in the Superstition Mountains east of Phoenix. He ended up at the YMCA Center in Phoenix and was befriended by Art Webber, one of the founding members of the Don’s Club of Arizona.

Storm advertised for adventurers in the local newspapers in January, 1937, to accompany him on a prospecting trip. This was Storm’s way of raising venture capital for his prospecting. Storm also wanted to author a small booklet with hopes of generating more income. He continued to run advertisements in various newspapers in Arizona and California hoping to attract partners with enough capital to finance his various mining expeditions into the Superstition Mountains.

Early in 1938, while prospecting near Aguila, he hurriedly put together a book titled Gold of the Superstitions which he published by the summer of that year. He had limited success with this booklet, but believed he could do a better job if he could find a backer who would support him for a future book. Barry Storm just happened to enter the Goldwater’s Store in Phoenix in the late spring of 1938, and by accident he met Barry M. Goldwater, a young entrepreneur and an amateur photographer.

Goldwater was only twenty-eight years old at the time. Storm talked Goldwater into accompanying him on a hike into the Superstition Mountains and told his story to Goldwater, convincing him to invest in his next book. Goldwater financed Barry’s book On the Trail of the Lost Dutchman.

Some old-timers might have wondered why Goldwater would have supported Storm with his book writing venture. Goldwater once said he was very moved by Storm’s enthusiasm to search for lost gold and treasure. Just prior to Storm walking into Goldwater’s store, Barry Goldwater had witnessed the success of Oren Arnold’s book advertised at the Korrick’s Department Store in downtown Phoenix. Why not, he had thought!

Barry Goldwater also did all the photography for Storm’s book. Storm further convinced the Don’s Club through Art Webber to use his handsome gold currency covered book for their 1939 Superstition Mountain Gold Trek. The club thought it was a worthwhile adventure and involved Barry Storm with their Superstition Mountain Trek for 1939.

Senator Barry Goldwater once remarked, “The man borrowed my name and some money, but I enjoyed the experience with him in the mountains photographing his dreams.”

Soon after Storm’s experience with Goldwater he met a man named Fisher who had developed an electronic device for locating mineral deposits, but needed somebody to test it.

Somehow Storm convinced Fisher he was his man. Storm took the M-Scope into the Superstition Mountains and tried it out. He claimed the Fisher Scope located the Peralta Land Grant Lost Mine in 1940. The publicity resulting from these claims launched Storm’s career as a mining expert and author. Storm was a so-called self-educated mining man. He had very little or no actual underground mining experience. He had no formal geology training. He claimed to have enormous knowledge about ancient European (Spanish) mining.

One of Storm’s best attempts at writing was his book Thunder God’s Gold in 1945. He wrote most of this book at Tortilla Flat after serving a short hitch in the United States Army Air Corps from 1943-1944.

The first time I heard the name Barry Storm I was a very young lad. My father and his friend Bill Cage were discussing the merits of Barry Storm’s book Superstition Gold in 1945, just before Storm’s book Thunder God’s Gold was published in that same year.

Prior to Storm’s book there were few publications that mention Jacob Waltz, the Peraltas or the Lost Dutchman Mine. The publications of Oren Arnold, Will Robinson, Mike Burns, Irwin Lively and a couple of other authors had tried to explain the mystery of the Superstition Mountain and its alleged lost gold mine. These authors took a more romantic view of the Superstition Mountains. Storm was the first to capture the story in an armchair adventure form. The reader could actually experience Storm’s excitement as he wrote about the Peraltas and the Lost Dutchman Mine. Other than Oren Arnold, none of the other authors were as popular or as well circulated.

It was Storm’s Thunder God’s Gold that really took center stage when Columbia motion pictures decided to make a film based on the book in 1948. When Lust for Gold appeared in theaters the story of the Lost Dutchman Mine became part of the national spotlight.

Not since the disappearance of Dr. Adolph Ruth in 1931 had the subject of this lost mine received such national interest. Storm wasn’t happy with how he was portrayed in the film. Columbia had portrayed him as the son of Jacob Waltz. Storm sued Columbia therefore delaying the release of the film for two years. The film still portrayed Storm as Waltz’s grandson when it was released in 1950.

Barry Storm was certainly one of “Coronado’s Children.” He continued to chase lost gold mines and treasures the rest of his life. He was a confirmed bachelor and always lived alone. Storm traveled annually to promote the sales and distribute his books.

Barry Storm spent most of his life chasing a dream. One of the last times I visited with him was at the Bluebird Mine and Curio Shop in 1967. We sat out front in some old chairs and talked about Superstition Mountain and the Lost Dutchman Mine, the Peralta Mine and even the mysterious stone maps.

Barry still dominated the stage of western storytellers. He was just as dramatic about telling his story whether it was with one or fifty listeners. For the most part Barry Storm lived his life like a dream, always believing he would strike it rich in some way.

The later years of his life were spent on a mining claim near Chiraco Summit, California. It was there he believed he would strike it rich with his Storm-Jade mine.

Barry was quite paranoid. He always believed somebody was out to kill him or steal his mine. He always carried a firearm.

I visited Barry at his Jade mine in 1969. We were in the area to attend the Indio Sidewinder Cruise with the Indio Jeep Club. He hadn’t changed any since I had visited with him at the Bluebird Mine and Curio Shop north of Apache Junction on the Apache Trail in 1967.

Barry corresponded with a variety of Dutch hunters around the country expounding his theories about lost gold in the Superstitions and other places around the country. Barry Storm was one of those everlasting characters that legends were formed around. Barry impacted the Lost Dutchman Mine story more than any other individual.

When I visited Barry at his mining claim I knew he was quite ill. The next thing I heard was when he passed away in the Veteran’s Hospital in San Diego on January 5, 1971. This sage of lost gold and treasure history had passed on leaving a dramatic legacy on the stage of the American Southwest.

Monday, September 19, 2016

Secrets of the Missing

September 12, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

The past five or six decades have produced a variety of missing person reports within the contemporary boundaries of the Superstition Wilderness Area. Many of these missing persons show up at home or in another state claiming they didn’t think any one would miss them. A majority of these missing person reports are resolved with telephone calls between relatives of the missing person. However, there are those reports that defy explanation and no clues have ever been found. Many involved strange incidents involving prospectors and treasure hunters.

The past five or six decades have produced a variety of missing person reports within the contemporary boundaries of the Superstition Wilderness Area. Many of these missing persons show up at home or in another state claiming they didn’t think any one would miss them. A majority of these missing person reports are resolved with telephone calls between relatives of the missing person. However, there are those reports that defy explanation and no clues have ever been found. Many involved strange incidents involving prospectors and treasure hunters.

Some of these missing person cases are actually very

bizarre. For example, Adolph Ruth was reported missing in early June of 1931.

The mountains were searched for almost eight weeks in the hottest part of the

summer. Yet, no sign of Ruth was discovered. On December 10, 1931, Ruth’s skull

was found near the First Water-Charlebois Trail just north of Bluff Springs

Mountain and south of the Red Hills. The rest of his skeletal remains were

found January 6, 1931. Ruth’s death was responsible for much speculation,

ranging from suicide, accidental death, to homicide. His death still confuses

many and its cause is still speculated.

Charlie Williams was reported missing four or five years

after Ruth. Williams was a World War I veteran who went into the Superstition

Mountains searching for gold on January 5, 1935. Williams was soon reported missing, but on

January 8, 1935, Williams stumbled out of the mountains with a pocket full of

gold nuggets telling a weird tale about being injured and not remembering

anything. Eventually Williams’ gold was confiscated by the United States

Government because it was dental gold, not natural gold. Williams was never

charged for illegal possession of gold, but again there was a tremendous amount

of speculations about his disappearance.

How many people are still missing in the Superstition

Wilderness? I am not sure if any are officially missing. A young man named Adam

Scott was reported missing on June 7, 1982. A sheriff’s posse searched for

almost a week before the search was called off. The search was called off when

the young man was reported seen near Roosevelt Lake. Scott remained missing

until March 25, 1996. This is when a local resident discovered skeletal remains

on an exploration flight over the wilderness area in 1996.

Scott was first reported missing in the Horse

Mesa Dam area. Robert Schoose and Barry Wiegle were making an exploration

flight in a Bell Ranger when Schoose spotted bones on a talus slope. For some

reason Schoose was convinced the bones could be human bones. A few days later

Schoose asked me about missing people in the Superstition Wilderness Area. The

only person I could think of at the time was Adam Scott. He had been reported

overdue on a hiking venture in to the area around Fish Creek Mountain and

Bronco Butte in June of 1982. The bleached bones Schoose spotted on the talus

slope below a small cave turned out to be the skeletal remains of Adam Scott.

Finally there was closure for Scott’s family. Adam had been missing for more

than fourteen years. When does a missing person in the Superstition

Wilderness become a cold case? Is it after six months, twelve months or several

years?

I met an old man many years ago that swore his son

was missing in the Superstition Wilderness Area. He believed his son was being

held prisoner because he knew the location of the Dutchman’s lost mine. I know

he harassed the Pinal County Sheriff’s Office about his son off and on for

about a year. He was totally convinced his son was somewhere in the

Superstition Wilderness and he wanted somebody to help him search for the boy. After talking to the gentleman I was doubtful he

even had a living son. I think he wanted to believe his son was alive and

searching for him eased the pain of his son’s actual death.

The loss of a loved one sometimes confuses

reality for a person. He was so convincing about his son I almost went into the

mountains to help look for him.

The following is a case of a missing person that is very difficult to determine.

Christmas, 1987, I remembered a man reporting his son missing near First Water. He claimed they were deer hunting and his son just vanished. The Sheriff’s Office started a search two days before Christmas and continued the search through Christmas. I volunteered to help because I knew the area quite well. My father and I had camped in the region quite often back in the late 1940s.

I knew where many of the old abandoned mine

holes and tunnels were located in the area. Many of the old tunnels were

camouflaged for various reasons. As it turned out the young man was mad at his

father and wanted to teach him a lesson. He hid in an abandoned tunnel

for almost five days. He was eventually found hiding in a small mine tunnel. He

was wet, cold and tired. He felt he had taught his father a lesson when

interviewed. He also cost the Sheriff’s Office a lot of money and aggravated a

lot of men who had to be away from home on Christmas searching for this young

man.

A very similar case occurred on July 25, 1998,

when Guy Garlinghouse was reported missing in the Superstition Wilderness Area

near Peralta Trailhead.

Temperatures were soaring to 114 degrees F that week. Apache Junction Search & Rescue, Pinal County Sheriff’s Posse and many volunteers combed the rugged hot desert around Peralta Trailhead searching for Mr. Garlinghouse.

Garlinghouse walked into the sheriff’s rescue

center at Peralta Trailhead six days later. He was a little sun burned but

otherwise in good shape. How did he survive in the desert for six days without

adequate water in such extreme temperatures unless he planned on being “lost”?

Again, this young man was aggravated with his parents and decided to worry them

a little. I never heard how this case was finally adjudicated.

|

| The mysterious Superstition Mountains with cloud cover. |

One of my students from a class I taught for the

college was reported missing. He often hiked Siphon Draw and the Flat Iron. A

search was conducted for Lee Krebs for six days before they found his body in

No-Name Canyon in December, 1978. He had slipped on clear ice and fell over a

ledge dropping some five hundred feet to his death. Lee was a retired

homebuilder and a well known community worker who really cared about Apache

Junction during a period when there was a lot of turnmoil. When he was first

reported missing everyone was quite sure he was allright. He was a veteran

outdoorsman and hiker. A quick moving winter storm caught him off guard while

up on the Flat Iron.

Over the years I have written several columns

about the missing and those who have disappeared. I would say ninety-nine per

cent of the missing person reports in the Superstition Wilderness have been

solved. Undoubtedly there are still a few unsolved cases involving the

wilderness. Some cases date back to the turn of the century. I have reviewed just a few of the hundreds of

missing person cases involving the wilderness area. Rest assured most of these

cases have been solved.

A region as rugged and isolated as the

Superstition Wilderness Area can certainly hold secrets of missing people that

remain unsolved today. Many of the so-called “missing people” may have just

walked in one end of the wilderness and out the other end. Therefore we have

the “Secrets of the Missing.”

Monday, September 12, 2016

Stranger Than Fiction

September 5, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

You can’t imagine the surprising and unbelievable stories I have heard over the past many scores of years. The tales of gold and treasure lost among the deep canyons and towering spires within the wilderness of Superstition Mountain are numerous. These tales stir the souls of men both young and old.

You can’t imagine the surprising and unbelievable stories I have heard over the past many scores of years. The tales of gold and treasure lost among the deep canyons and towering spires within the wilderness of Superstition Mountain are numerous. These tales stir the souls of men both young and old.

The search for adventure has filled the hearts

of many who have followed in the footsteps of “Coronado’s Children” as told by

Frank J. Dobie. When Dobie penned his book in 1941 he could not have imagined

the impact his words would have on a generation of young men who pursued the

treasure trail.

I choose not to follow each and every one of these stories, however some are stranger than fiction itself. The following story is buried in the pages of a journal written forty years ago about an event that occurred in the Superstition Mountains.

Since the first Anglo-Americans laid their eyes

upon the rugged façade of Superstition Mountain there were stories about lost

gold in those mountains. Those who believe these stories can’t be deterred with

facts or even common sense. They will continue their search until they can no

longer walk or ride the trails of these rugged mountains. There are but a

few people who understand this devotion and dedication to a belief and a dream.

Over the years I have had many friends who were

devoted believers in this lost gold in the Superstition Mountains. I had one

particular friend whom I wanted to believe his story so badly, but I just

couldn’t accept the facts he had gathered to support his theory. I would never

discourage, but I never really encouraged him either until I realized his life

hung in the balance. His dream of riches kept him alive. He would swear me to

secrecy and then tell me things he actually saw in the mountains.

“Tom,” he said. “I was hiking up this narrow canyon

when I saw a cave in a side canyon. I climbed over large boulders and made my

way to the entrance of the cave. I could see the cave had been use many years

before. I had a decent flashlight so I started exploring the cave. Near the

rear of the cave was a small shaft that dropped down about five feet. The cave

then opened into a large chamber filled massive crystalline rock. In one corner

of the chamber there was more gold bullion and artifacts than the mind could

imagine. There were hundreds of pounds of gold in bars, statues and even

nuggets as big as chicken eggs. I was so excited and disoriented I didn’t

realize my flashlight batteries were about to die. All of a sudden I was in

total darkness with no light. I was not sure which direction it was to the

entrance. Finally I gained enough composure I remembered have some matches. I

struck a match and saw the tunnel I had followed down into this chamber.

“I immediately headed for what I believed was

the exit. The only specimen I kept was a nugget about the size of a small

chicken egg. Striking one match at a time I finally made my way out of the

tunnel. Once I reached the entrance the sun had set and it was dark. I picked

up my pack and walking stick and made my way down the canyon and back to the

trail.

|

| Searching in extremely rugged territory, Karl Duess leads a pack horse through the storied terrain of Tortilla Mountain. |

“I found a place along the trail to pitch camp

for the rest of the night. The next morning at sunrise I thought I would try to

retrace my steps back to the cave and the treasure I had found. “Tom, I never could find the treasure cave

again. As I sat under an old Mesquite in Needle Canyon I thought maybe I had

dreamed this story and it wasn’t real. Then, when I reached into my pocket and

felt the nugget the size of a chicken egg I was convinced it was not a dream.

For past decade I have tried to find that treasure cave in the Superstition

Wilderness Area.”

Twenty years ago old Joe showed me that chicken egg

size nugget of quartz and gold. I would say there was about five ounces or more

of gold in the nugget. Even as I looked at the nugget Joe was showing me I still really didn't believe his story, but then again "truth can be stranger than fiction."

Monday, September 5, 2016

Trail of Tears

August 29, 2016 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

The Superstition Wilderness Area and Superstition Mountain in particular have been an attraction to human kind for more than a millennium. First came the Native Americans who found the region conducive to their way of living. Hunting and gathering was their main means of survival. The region offered numerous caves for shelter. Their ruins today are a mute testimony to their early occupancy of this rugged mountain region in Central Arizona.

The Superstition Wilderness Area and Superstition Mountain in particular have been an attraction to human kind for more than a millennium. First came the Native Americans who found the region conducive to their way of living. Hunting and gathering was their main means of survival. The region offered numerous caves for shelter. Their ruins today are a mute testimony to their early occupancy of this rugged mountain region in Central Arizona.

Death was no stranger to these early inhabitants

of this rugged mountain wilderness. Many lost their lives to accidents, animal

attacks and other warring groups that mounted raids into their homelands. Of

course all these deaths were pre-historical without documentation. The

excavation of a couple of sites adjacent to the wilderness area suggests some

of these early Native Americans died from wounds caused by an adversary.

An Apache Junction resident was excavating for a

pool in his yard when he came across a burial site on his property. The skull

that was found in the grave had severe damage from blunt force trauma. The ulna

and radius bones of the arm and clavicle bone of the shoulder had sharp

knife-like marks indicating an attack that was defended with the individual’s

arms. These injuries were probably the results of a battle with a raiding party

that ended in the demise of this individual several thousand years ago.

This Native American was probably one the earliest people to die in this vast

mountain wilderness we call the Superstitions today.

The Superstition Mountain region has a long history

of missing people, homicides, accidental deaths, and injuries. The earliest

recorded history of these events occurred when the infantry companies were sent

out of Camp McDowell to quell the raids of the Apache-Yavapai who lived in the

Superstition Mountains (Salt River Mountains) and Pinaleno (Pinal) Mountains in

the 1860’s.

The Army effectively used the Pima Scouts against the Apache-Yavapai during this era. Several hundred Apache-Yavapai were slain in their Rancherias or villages throughout the Superstition Mountain area at places such as Pinon Camp (near Weaver’s Needle) May 11, 1867, Dismal Valley (Tortilla Ranch area), March 14, 1868, and Tortilla Creek near Tortilla Flat later in that year.

Also several smaller villages were destroyed and the males were killed. The Pimas took the captured Apache-Yavapai women and children into slavery. The Pima Scouts clubbed the Apache-Yavapai old and young males to death. Armed Pima Scouts and soldiers shot those who tried to escape.

|

| The Tortilla Ranch area of the Superstition Wilderness was known as Dismal Valley. It served as a large Native American village in the 1870’s. |