April 22, 2013 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

There are many stories about unusual places in the Superstition Wilderness Area. Since the late 1940’s, Hidden Canyon has been a mysterious place we have heard stories about and wanted to visit. For many years I believed this canyon to be nothing more than a big, windy story. The reason being I couldn’t locate it. Also I have had several individuals tell me they have been there, but couldn’t give me directions to its location for a variety reasons. Another friend said he knew where the canyon was and he believed it was named after Bill Hidden, an old time prospector of the Superstition Wilderness Area who often camped there.

Some time around 1963, I came across a contemporary map sketched by some Dutch hunter named Darrel Warren who claimed his grandfather had drawn the Barlett-Warren Map describing the location of Hidden Canyon. I thought at first, this was just a coincidence. I ended up with a copy of this map and filed it away. Thirty years later, Greg Davis located another copy of this map and gave it to me. I examined both maps and found there were several discrepancies in the two maps indicating more than one author.

The names of historical landmarks have a way of being changed for various or obvious reasons. Each generation will often start on a campaign of changing local landmarks. A good example of such changes is city and county street names. Such roads as Idaho, Meridian, Ironwood and Lost Dutchman Boulevard all had different names thirty years ago. Does anyone remember where Wilson Drive was, or how about Transmission Road, or County Line Road and Moeur Road?

Not so many years ago a gentleman from eastern Texas contacted me concerning the location of a street in Apache Junction his grandmother once lived on in 1946. He told me his grandmother buried a couple of quart jars full of gold coins. He knew this to be true because his grandparents were Depression era people and didn’t trust banks. They retired in Apache Junction at the encouragement of Julian King and the street they supposedly lived on was called Rattlesnake Lane. Unfortunately, the name of the street his grandmother lived on is lost in the pages of Apache Junction history.

Tracing down landmarks that have been changed is a major undertaking. If names are changed they should be properly archived somewhere so references can be made back to them. If the East Texas man’s story was true there are a couple of one-quart fruit jars full of gold coins near Rattlesnake Lane in Apache Junction, Arizona.

The same fate is exactly what happened to Hidden Canyon. The name Hidden Canyon probably originated unofficially and was a name used by prospectors and cattlemen around the turn of the 20th century.

According to Floyd Stone, Hidden Canyon was used in the early days to corral range horses in before a roundup. The canyon supposedly was located in what is now known as Horse Camp country east of La Barge Canyon. The canyon had a narrow entrance, but opened up into an area of about 40 acres. There was a small stone cabin with a tin roof and corral within this small valley. The site was located near the base of an intermittent waterfall. There was a small water seep that provided a dependable water supply year-round. This was an ideal site for a prospector or range cowboy to set up camp. Down through the decades this site has been forgotten.

As far as I know, Hidden Canyon remains lost to this day. Often I think this story has been confused with the Lost Adams Diggings located in Eastern Arizona or Western New Mexico. There were stories about a lost gold mine associated with this site, just like the lost gold on Rattlesnake Lane in Apache Junction.

My father always said there was a very thin line between legend and truth. Actually he called it a thin gray line. After all isn’t that what legends and tales are about?

By Tom Kollenborn © 2022 Courtesy of the Apache Junction News and Apache Junction Public Library

Monday, April 29, 2013

Monday, April 22, 2013

A Day at the Ranch

April 15, 2013 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Some time ago somebody asked me what it was like living at the Quarter Circle U Ranch in the late 1950’s. I thought about it for a minute and said, "I was quite young and wanted to be a cowboy. Electricity and running water were not that important to me."

However, at the same time, I must admit life was quite primitive at the ranch. We cooked on a wood stove and a propane two-burner stove. We had a Serval Freezer that ran on propane. We had a single water pipe in the kitchen. That is when there was water in the tank. Our water depended on a full tank of water pumped in by a windmill. The windmill was dependent on a breeze to operate. The problem with wind on the ranch was you either had not enough or too much.

No, we didn’t have fans or coolers. How did we survive in 110 degree days? It wasn’t easy, but we were young and foolish. I will try to describe what it was like working on the old Quarter Circle U Ranch.

We were usually up by 4:30 a.m. to feed the stock in the corrals. This would include our riding horses and cattle that were being treated for various ailments or injuries. Every animal was important for us to save. After feeding the stock, we fed our chickens and then the two dogs. The dogs were stock dogs and they helped us get cattle out of the brush and other inaccessible locales. While I fed, my partner, Mike, would begin breakfast and also prepare a pot of beans to cook on the wood stove. Mike and I would alternate jobs during our morning routine.

By the time I was finished with morning chores, that included gathering our eggs for breakfast, I was ready to return to the ranch house.

We generally had bacon, potatoes, chili, and eggs for breakfast. We had to slice our own bacon so the slices were often quite thick. Our bean pot had beef, bacon, and chili in it. We quickly learned to keep a stone on the bean pot lid. If we didn’t we would have a mouse in our bean pot. Just more protein if you’re a hungry cowboy after a day of hard work.

After breakfast we would go down to the barn and corral to prepare for our day ahead. During the summer months we generally worked from about 6:00 a.m. until about 2:00 p.m. at which time we would shade up. We would then go back to work at about 5:00 p.m. working for another couple hours or so.

Summer days were long days no matter how you looked at the work agenda. Usually we were fixing fence, repairing water sources, checking stock or packing salt.

When we worked for the Barkley Cattle Company the ranch included one hundred and seventeen sections of state land, forestland and BLM land. We rode from Canyon Lake in the north to Peralta Road in the south. All of the Gold Canyon area was part of the ranch’s range with the exception of the King’s Ranch Guest Ranch and Resort.

The main headquarter’s ranch was located at the Three R’s Ranch. The old ranch headquarters was located just south of Apache Land Movie Studio. Everthing has changed in the area today. We often herded stocked from the U Ranch to the stone corrals at the Three R’s Ranch. The ride was about eight miles, but was slow and dusty with fifteen to twenty head of cattle.

Bill Barkley, Mike Finley and I drove about seventy-five head of yearlings along the old Three R’s – Quarter Circle U Trail in April of 1959. I think this was the last time the entire trail was used for a drive. Often along our route we had a mixture of Mule deer and Javelinas. The wildlife would eventually fade into the desert, but often stayed with us for a mile or so.

Once the spring roundup was over, branding, dehorning, castration, and doctoring was done and we then prepared for the long hot summer. We would return to the U-Ranch and have a little time to prepare for the hot summer ahead. First and most important was putting all of the bed legs in a tin can filled with motor oil to help keep scorpions out of our beds. The pesky creatures would then crawl up on the rafters in the roof and drop into our beds. We also dealt with black ants and mosquitos. Mosquitos were very common after the summer rains in July. Sleep at night could be very difficult in those days.

Another interesting place was the outside privy. The outhouse was a notoriously dangerous place for scorpions and an occasional rattlesnake. Scorpions often waited for an unsuspecting victim to sit down on a toilet seat and then greet him with painful sting. We soon learned to lift up the seat and check it for scorpions or whatever else might be waiting for us. Small rattlesnakes lying near the outhouse found it comfortable in a world of survival. I guess the old outhouse was cool. I eventually painted a sign for the outhouse that warned people of problems they might encounter there.

If we had any riding to do, like packing salt, we were up at 3 a.m. and would be on the trail by 5 a.m. I recall a trip we made to Bluff Springs in July to drop salt. Our plan was to be back at the ranch by 11 a.m. We would have made it, but we spent two hours working on the water source at Bluff Springs so the concrete tank could fill. Our ride back in temperatures that exceeded 110° F about did us in. We were sunburned and dehydrated by the time we arrived back at the ranch.

Life on the old ranch was rough, but I still recall all those adventures and it was probably one of the most exciting times of my life. I owe a lot to William Thomas Barkley for allowing me to have the opportunity to grow into manhood and learn what work was really about.

All ranches on the desert were like the old U Ranch of the Superstitions.

Some time ago somebody asked me what it was like living at the Quarter Circle U Ranch in the late 1950’s. I thought about it for a minute and said, "I was quite young and wanted to be a cowboy. Electricity and running water were not that important to me."

However, at the same time, I must admit life was quite primitive at the ranch. We cooked on a wood stove and a propane two-burner stove. We had a Serval Freezer that ran on propane. We had a single water pipe in the kitchen. That is when there was water in the tank. Our water depended on a full tank of water pumped in by a windmill. The windmill was dependent on a breeze to operate. The problem with wind on the ranch was you either had not enough or too much.

No, we didn’t have fans or coolers. How did we survive in 110 degree days? It wasn’t easy, but we were young and foolish. I will try to describe what it was like working on the old Quarter Circle U Ranch.

We were usually up by 4:30 a.m. to feed the stock in the corrals. This would include our riding horses and cattle that were being treated for various ailments or injuries. Every animal was important for us to save. After feeding the stock, we fed our chickens and then the two dogs. The dogs were stock dogs and they helped us get cattle out of the brush and other inaccessible locales. While I fed, my partner, Mike, would begin breakfast and also prepare a pot of beans to cook on the wood stove. Mike and I would alternate jobs during our morning routine.

By the time I was finished with morning chores, that included gathering our eggs for breakfast, I was ready to return to the ranch house.

We generally had bacon, potatoes, chili, and eggs for breakfast. We had to slice our own bacon so the slices were often quite thick. Our bean pot had beef, bacon, and chili in it. We quickly learned to keep a stone on the bean pot lid. If we didn’t we would have a mouse in our bean pot. Just more protein if you’re a hungry cowboy after a day of hard work.

After breakfast we would go down to the barn and corral to prepare for our day ahead. During the summer months we generally worked from about 6:00 a.m. until about 2:00 p.m. at which time we would shade up. We would then go back to work at about 5:00 p.m. working for another couple hours or so.

Summer days were long days no matter how you looked at the work agenda. Usually we were fixing fence, repairing water sources, checking stock or packing salt.

When we worked for the Barkley Cattle Company the ranch included one hundred and seventeen sections of state land, forestland and BLM land. We rode from Canyon Lake in the north to Peralta Road in the south. All of the Gold Canyon area was part of the ranch’s range with the exception of the King’s Ranch Guest Ranch and Resort.

The main headquarter’s ranch was located at the Three R’s Ranch. The old ranch headquarters was located just south of Apache Land Movie Studio. Everthing has changed in the area today. We often herded stocked from the U Ranch to the stone corrals at the Three R’s Ranch. The ride was about eight miles, but was slow and dusty with fifteen to twenty head of cattle.

Bill Barkley, Mike Finley and I drove about seventy-five head of yearlings along the old Three R’s – Quarter Circle U Trail in April of 1959. I think this was the last time the entire trail was used for a drive. Often along our route we had a mixture of Mule deer and Javelinas. The wildlife would eventually fade into the desert, but often stayed with us for a mile or so.

Once the spring roundup was over, branding, dehorning, castration, and doctoring was done and we then prepared for the long hot summer. We would return to the U-Ranch and have a little time to prepare for the hot summer ahead. First and most important was putting all of the bed legs in a tin can filled with motor oil to help keep scorpions out of our beds. The pesky creatures would then crawl up on the rafters in the roof and drop into our beds. We also dealt with black ants and mosquitos. Mosquitos were very common after the summer rains in July. Sleep at night could be very difficult in those days.

Another interesting place was the outside privy. The outhouse was a notoriously dangerous place for scorpions and an occasional rattlesnake. Scorpions often waited for an unsuspecting victim to sit down on a toilet seat and then greet him with painful sting. We soon learned to lift up the seat and check it for scorpions or whatever else might be waiting for us. Small rattlesnakes lying near the outhouse found it comfortable in a world of survival. I guess the old outhouse was cool. I eventually painted a sign for the outhouse that warned people of problems they might encounter there.

If we had any riding to do, like packing salt, we were up at 3 a.m. and would be on the trail by 5 a.m. I recall a trip we made to Bluff Springs in July to drop salt. Our plan was to be back at the ranch by 11 a.m. We would have made it, but we spent two hours working on the water source at Bluff Springs so the concrete tank could fill. Our ride back in temperatures that exceeded 110° F about did us in. We were sunburned and dehydrated by the time we arrived back at the ranch.

Life on the old ranch was rough, but I still recall all those adventures and it was probably one of the most exciting times of my life. I owe a lot to William Thomas Barkley for allowing me to have the opportunity to grow into manhood and learn what work was really about.

All ranches on the desert were like the old U Ranch of the Superstitions.

Monday, April 15, 2013

The Passing Of The Concord

April 8, 2013 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

The history of the Concord stages along the Apache Trail was very brief. The Concord stages were used only between 1906-1910. Other stagecoaches were used independently until about 1917. However, by 1915 horse drawn vehicles were, for the most part, replaced by self-propelled vehicles.

"Mesa-Roosevelt Contract Expires," read the Arizona Republican on March 23, 1910. This was the end of an era. The government contract to carry the United States mail to Roosevelt Dam from Phoenix officially expired on July 1, 1910. Roosevelt Dam was nearing completion and the self-propelled vehicle was replacing team-drawn wagons and stages along the Mesa-Roosevelt Road (Apache Trail).

According to the article, horse-drawn vehicles were giving way to the railroads, trolley lines and light self-propelled vehicles. It was apparent that the Mesa-Roosevelt Road was going to change. Since the completion of the Mesa-Roosevelt Road Mesa residents were accustomed to seeing Concord stages drawn by four horses going and coming daily from Roosevelt. The Concords had been an important part of the West. They linked the distant Arizona towns together and provided a means in which to carry the mail. It was the mail contracts that kept these stage lines going.

The newspaper article also predicted there would be stagelines still in use in Arizona for years to come. But the development of better roads and shorter hauls soon led to the use of lighter vehicles and self-propelled vehicles.

The Mesa-Roosevelt Stage Company was capitalized in 1906 at $25,000 and held mail contracts that necessitated covering 334 miles daily by their drivers. The contract between Mesa and Roosevelt was the most important one. The trip from Mesa to Roosevelt required ten hours road travel to cover the sixty miles over mountainous roads. Forty-five head of horses were kept at the various stations along the route. One of the greatest management problems for stage lines was to haul feed to each of the stations. Horses and feed were kept at several stations along the Apache Trail. These stations included locations at Mesa, Desert Well, Hall’s Station, Government Well, Tortilla Flat, Fish Creek, and Roosevelt.

During the four years of operation from 1906-1910, there was not a single fatality on the line due to any accidents, and there were some serious accidents. In one accident a stage plunged over a sixty-foot embankment breaking the legs of the driver, Frank Nash. With all the runaways, tip-overs and trips down Fish Creek Hill on two wheels, it’s a wonder these pioneers didn’t have a cemetery at each of the stage stations along the Mesa-Roosevelt Road. The safety record attests to the quality of the Concord coaches, including their ruggedness and durability.

The lighter wagons and self-propelled vehicles slowly changed the Mesa-Roosevelt Road (Apache Trail). The historic road witnessed the transition from horse-drawn vehicles to modern automobiles under conditions involving narrow roads, rough roads, sharp curves and steep grades.

Today, the Apache Trail remains as a monument to those early pioneers who contributed so much of their time and energy to the building of the Apache Trail and Roosevelt Dam. Take your time and enjoy your drive to Roosevelt Dam over the Apache Trail. It’s still 44 miles of rugged, adventurous, scenic wonder.

The history of the Concord stages along the Apache Trail was very brief. The Concord stages were used only between 1906-1910. Other stagecoaches were used independently until about 1917. However, by 1915 horse drawn vehicles were, for the most part, replaced by self-propelled vehicles.

"Mesa-Roosevelt Contract Expires," read the Arizona Republican on March 23, 1910. This was the end of an era. The government contract to carry the United States mail to Roosevelt Dam from Phoenix officially expired on July 1, 1910. Roosevelt Dam was nearing completion and the self-propelled vehicle was replacing team-drawn wagons and stages along the Mesa-Roosevelt Road (Apache Trail).

According to the article, horse-drawn vehicles were giving way to the railroads, trolley lines and light self-propelled vehicles. It was apparent that the Mesa-Roosevelt Road was going to change. Since the completion of the Mesa-Roosevelt Road Mesa residents were accustomed to seeing Concord stages drawn by four horses going and coming daily from Roosevelt. The Concords had been an important part of the West. They linked the distant Arizona towns together and provided a means in which to carry the mail. It was the mail contracts that kept these stage lines going.

The newspaper article also predicted there would be stagelines still in use in Arizona for years to come. But the development of better roads and shorter hauls soon led to the use of lighter vehicles and self-propelled vehicles.

The Mesa-Roosevelt Stage Company was capitalized in 1906 at $25,000 and held mail contracts that necessitated covering 334 miles daily by their drivers. The contract between Mesa and Roosevelt was the most important one. The trip from Mesa to Roosevelt required ten hours road travel to cover the sixty miles over mountainous roads. Forty-five head of horses were kept at the various stations along the route. One of the greatest management problems for stage lines was to haul feed to each of the stations. Horses and feed were kept at several stations along the Apache Trail. These stations included locations at Mesa, Desert Well, Hall’s Station, Government Well, Tortilla Flat, Fish Creek, and Roosevelt.

During the four years of operation from 1906-1910, there was not a single fatality on the line due to any accidents, and there were some serious accidents. In one accident a stage plunged over a sixty-foot embankment breaking the legs of the driver, Frank Nash. With all the runaways, tip-overs and trips down Fish Creek Hill on two wheels, it’s a wonder these pioneers didn’t have a cemetery at each of the stage stations along the Mesa-Roosevelt Road. The safety record attests to the quality of the Concord coaches, including their ruggedness and durability.

The lighter wagons and self-propelled vehicles slowly changed the Mesa-Roosevelt Road (Apache Trail). The historic road witnessed the transition from horse-drawn vehicles to modern automobiles under conditions involving narrow roads, rough roads, sharp curves and steep grades.

Today, the Apache Trail remains as a monument to those early pioneers who contributed so much of their time and energy to the building of the Apache Trail and Roosevelt Dam. Take your time and enjoy your drive to Roosevelt Dam over the Apache Trail. It’s still 44 miles of rugged, adventurous, scenic wonder.

Monday, April 8, 2013

Fire Season in the Desert

April 1, 2013 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

The beauty of the Sonoran Desert after a wet spring is fabulous. This past winter has been witness to a little more precipitation than usual, even some snow! Due to this precipitation there will be more abundant weed growth and a lot of the older dead growth will provide fuel for the slightest spark whether accidental, careless or natural.

Once the temperatures get up over 100 degrees the desert becomes a tinderbox ready to explode. A dry desert is often marred with dangerous wildfires in the late spring and the early summer months prior to the monsoons. The fire danger increases as the temperatures increase. The wild fire season also increased dramatically as more and more people move to the arid deserts of the American Southwest. Many of these new residents don’t realize the extreme danger of a dry desert under the extreme high temperatures of summer. This desert tinder can be as volatile as gasoline.

Most wildfires result from two things. Lightning and human carelessness. Lightning strikes usually occur during the July monsoons and most fires prior to the monsoons are usually human caused. It is often a carelessly tossed cigarette, careless target shooter or an abandoned campfire that causes these fires. We can’t over emphasize how a carelessly tossed cigarette could cost you your home and your life.

As we move into summer, families are beginning their summer vacations and outdoor activities. These activities include backyard cookouts, camping, and other outdoor activities. Any of these enjoyable activities can lead to disaster if we are careless with fire.

I have witnessed many major wild fires in our area over the years. The first real wild fire I recall occurred in July, 1949. This fire raged out of control east of Reavis Ranch for several days before it was brought under control. Another wild fire broke out west of Roosevelt Lake in the Pinyon Mountain area in 1959, and burned several thousand acres of the Tonto National Forest before it was contained. Lightning caused these fires.

A fire broke out south of the Reavis Ranch in 1966, destroying much of the Ponderosa pine forest in the area. This fire was known as the Iron Mountain Burn and was attributed to a campfire. The forest service planted drought resistant grasses in the area to prevent soil erosion. This grass has become the climax vegetation in the area today.

A large wild fire raged through Needle Canyon in 1969 destroying several thousand acres of desert landscape. An abandoned campfire was the likely cause of this wild fire. This fire eventually burned itself out because of the inaccessibility of firefighters to the area.

I witnessed and photographed one of the most dramatic wild fires on the slopes of Superstition Mountain in the summer of 1979. This fire raged across the slopes of Superstition Mountain with a fifty-foot wall of flame engulfing everything in its path. This fire was caused when a high wind blew over a charcoal grill in somebody’s yard near the base of the mountain. One careless neighbor endangered hundreds of lives and millions of dollars worth of property as the fire spread over the mountain within an hour. The smoke was so thick Superstition Mountain could not be seen from State Route 88 (Apache Trail). If it had not been for slurry bombers many homes would have been lost in this fire and lives could have hung in the balance.

On July 4, 1983 another major fire raged on the eastern side of Superstition Mountain destroying several thousand acres. This fire eventually burned its self out. Needle Canyon was struck with another wildfire in March of 1984. This fire burned up the northeastern side of Bluff Springs Mountain and eventually also burned itself out. Abandoned campfires most likely caused these fires.

There was a large wildfire in the area of the Massacre Grounds and along the northwestern slopes of Superstition Mountain the following month in April of 1984. This fire was contained and in some areas burned itself out. Several other man-made fires occurred in the wilderness or around Superstition Mountain between 1984 and 1994.

The next big fire to strike the region was the Geronimo blaze near the Gold Canyon development area. This fire started around June 11, 1995, and was fought for three days. One hundred and twenty firefighters eventually brought this blaze under control before property or lives were lost. The fire destroyed twenty-three hundred acres and threatened several homes near Gold Canyon worth more than a hundred thousand dollars each. This particular fire produced huge columns of smoke that could be seen from Phoenix skyscrapers.

The Lone fire on Four Peaks came near the end of April 1996. The Lone fire destroyed almost sixty-two thousand acres of the Tonto National Forest. To put this figure in perspective, this would be almost one third of the Superstition Wilderness Areas. This was one of the most devastating fires on public land adjacent to the Superstition Wilderness Area during the past twenty-five years.

Then, on June 18, 2002, one of the largest wildfires in Arizona history began. This was the Rodeo-Chediski Fire. This wildfire burned 470,000 acres of Arizona timber and grasslands by time it was under control July 7, 2002. Recovery from this fire will require more than a century.

The Wallow Fire in June of 2011 near Alpine burned more than 520,000 acres becoming the largest wildfire in Arizona history. The Wallow fire was human-caused. The Superstition Wilderness Area experiences some kind of a wild fire almost each summer. On several occasions the wilderness has been closed to camping and hiking during extreme fire conditions.

This historical accounting of wild fire in our area gives you some idea of what a potential fire hazard the desert can be between late April and mid July. Precipitation is often a double-edged sword. Rain always brings relief to a dry desert region reducing fire danger, but it always produced an abundant growth of brush that can create more fuel and cause more fires. Precipitation also causes severe erosion in areas that have been burned and denuded of vegetation. This in turn destroys the watershed that is so crucial to water conservation in an arid state like Arizona.

As the dry season approaches the fire danger will continue to escalate, bringing dangerous conditions to our desert. There is plenty of tinder and deadfall to burn on the desert. Once the high temperatures arrive and dry out the tinder it is extremely volatile.

Your care with fire, smoking, using firearms and open flames at all times is extremely important and will protect us all. Smoking should be confined to automobiles or building during extreme fire conditions. Your caution with fire protects everyone from immediate danger.

We can help by having reasonable firebreak around our homes, especially if we live on a large lot containing a lot of dry tinder. I would like to encourage everyone to be extremely careful with matches, cigarettes, outdoor cooking, power tools, and any other use of open flames or sparks. Fire safety in the desert starts at home and should be practiced at all times. For more information about fire safety around your home call the Apache Junction Fire District at 480-982-4445.

|

| An Apache Junction firefighter battles a wildfire on Superstition Mountain (file photo). Most wildfires result from two things— lightning and human carelessness. |

Once the temperatures get up over 100 degrees the desert becomes a tinderbox ready to explode. A dry desert is often marred with dangerous wildfires in the late spring and the early summer months prior to the monsoons. The fire danger increases as the temperatures increase. The wild fire season also increased dramatically as more and more people move to the arid deserts of the American Southwest. Many of these new residents don’t realize the extreme danger of a dry desert under the extreme high temperatures of summer. This desert tinder can be as volatile as gasoline.

Most wildfires result from two things. Lightning and human carelessness. Lightning strikes usually occur during the July monsoons and most fires prior to the monsoons are usually human caused. It is often a carelessly tossed cigarette, careless target shooter or an abandoned campfire that causes these fires. We can’t over emphasize how a carelessly tossed cigarette could cost you your home and your life.

As we move into summer, families are beginning their summer vacations and outdoor activities. These activities include backyard cookouts, camping, and other outdoor activities. Any of these enjoyable activities can lead to disaster if we are careless with fire.

I have witnessed many major wild fires in our area over the years. The first real wild fire I recall occurred in July, 1949. This fire raged out of control east of Reavis Ranch for several days before it was brought under control. Another wild fire broke out west of Roosevelt Lake in the Pinyon Mountain area in 1959, and burned several thousand acres of the Tonto National Forest before it was contained. Lightning caused these fires.

A fire broke out south of the Reavis Ranch in 1966, destroying much of the Ponderosa pine forest in the area. This fire was known as the Iron Mountain Burn and was attributed to a campfire. The forest service planted drought resistant grasses in the area to prevent soil erosion. This grass has become the climax vegetation in the area today.

A large wild fire raged through Needle Canyon in 1969 destroying several thousand acres of desert landscape. An abandoned campfire was the likely cause of this wild fire. This fire eventually burned itself out because of the inaccessibility of firefighters to the area.

I witnessed and photographed one of the most dramatic wild fires on the slopes of Superstition Mountain in the summer of 1979. This fire raged across the slopes of Superstition Mountain with a fifty-foot wall of flame engulfing everything in its path. This fire was caused when a high wind blew over a charcoal grill in somebody’s yard near the base of the mountain. One careless neighbor endangered hundreds of lives and millions of dollars worth of property as the fire spread over the mountain within an hour. The smoke was so thick Superstition Mountain could not be seen from State Route 88 (Apache Trail). If it had not been for slurry bombers many homes would have been lost in this fire and lives could have hung in the balance.

On July 4, 1983 another major fire raged on the eastern side of Superstition Mountain destroying several thousand acres. This fire eventually burned its self out. Needle Canyon was struck with another wildfire in March of 1984. This fire burned up the northeastern side of Bluff Springs Mountain and eventually also burned itself out. Abandoned campfires most likely caused these fires.

There was a large wildfire in the area of the Massacre Grounds and along the northwestern slopes of Superstition Mountain the following month in April of 1984. This fire was contained and in some areas burned itself out. Several other man-made fires occurred in the wilderness or around Superstition Mountain between 1984 and 1994.

The next big fire to strike the region was the Geronimo blaze near the Gold Canyon development area. This fire started around June 11, 1995, and was fought for three days. One hundred and twenty firefighters eventually brought this blaze under control before property or lives were lost. The fire destroyed twenty-three hundred acres and threatened several homes near Gold Canyon worth more than a hundred thousand dollars each. This particular fire produced huge columns of smoke that could be seen from Phoenix skyscrapers.

The Lone fire on Four Peaks came near the end of April 1996. The Lone fire destroyed almost sixty-two thousand acres of the Tonto National Forest. To put this figure in perspective, this would be almost one third of the Superstition Wilderness Areas. This was one of the most devastating fires on public land adjacent to the Superstition Wilderness Area during the past twenty-five years.

Then, on June 18, 2002, one of the largest wildfires in Arizona history began. This was the Rodeo-Chediski Fire. This wildfire burned 470,000 acres of Arizona timber and grasslands by time it was under control July 7, 2002. Recovery from this fire will require more than a century.

The Wallow Fire in June of 2011 near Alpine burned more than 520,000 acres becoming the largest wildfire in Arizona history. The Wallow fire was human-caused. The Superstition Wilderness Area experiences some kind of a wild fire almost each summer. On several occasions the wilderness has been closed to camping and hiking during extreme fire conditions.

This historical accounting of wild fire in our area gives you some idea of what a potential fire hazard the desert can be between late April and mid July. Precipitation is often a double-edged sword. Rain always brings relief to a dry desert region reducing fire danger, but it always produced an abundant growth of brush that can create more fuel and cause more fires. Precipitation also causes severe erosion in areas that have been burned and denuded of vegetation. This in turn destroys the watershed that is so crucial to water conservation in an arid state like Arizona.

As the dry season approaches the fire danger will continue to escalate, bringing dangerous conditions to our desert. There is plenty of tinder and deadfall to burn on the desert. Once the high temperatures arrive and dry out the tinder it is extremely volatile.

Your care with fire, smoking, using firearms and open flames at all times is extremely important and will protect us all. Smoking should be confined to automobiles or building during extreme fire conditions. Your caution with fire protects everyone from immediate danger.

We can help by having reasonable firebreak around our homes, especially if we live on a large lot containing a lot of dry tinder. I would like to encourage everyone to be extremely careful with matches, cigarettes, outdoor cooking, power tools, and any other use of open flames or sparks. Fire safety in the desert starts at home and should be practiced at all times. For more information about fire safety around your home call the Apache Junction Fire District at 480-982-4445.

Monday, April 1, 2013

Snakes Alive! - Snake Season

|

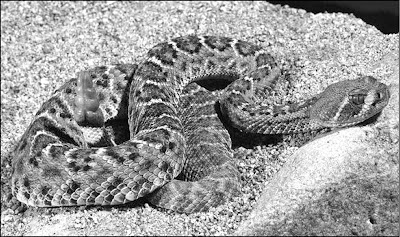

| The Western Diamondback is the most common venomous snake in the Apache Junction/Gold Canyon area. |

February 25, 2013 © Thomas J. Kollenborn. All Rights Reserved.

Spring is here, with temperatures climbing toward 100 degees already in March. Reptiles, meaning most cold-blooded animals, become very active when temperatures soar into the nineties. When it warms up in the spring it is wise to keep a keen eye open for rattlesnakes.

August and September are traditionally the most active months for rattlesnakes on the Sonoran Desert at elevations below 4,000 feet. Reptiles coming out of hibernation begin the search for food. In late fall when temperatures drop below seventy-eight degrees, reptiles begin to prepare for hibernation.

I have lived in the Sonoran Desert for many years and have encountered hundreds of rattlesnakes. Under most conditions a rattlesnake is very difficult to spot unless it is disturbed and moves. Rattlesnakes generally rattle before they move, but if the truth were really known, most people who walk or hike in the desert will walk by ten snakes for every one that they see.

A rattlesnake can be identified by the triangular-shape of its head and the rattle on its tail. A closer examination will reveal an elliptical-shaped pupil in its eye. This trait is common to poisonous snakes in the Sonoran Desert. All rattlesnakes will have a pit organ near the nostril orifice.

Rattlesnakes come in a variety of colors and patterns. Snakes found in our area will have rings around their tails above the rattles. The color of these rings will alternate between black and white in various shades and the visibility of these rings will depend on the species. The Western Diamond Back rattler’s rings are very pronounced and stand out, whereas the rings on an Arizona Black are not very visible because of the blending of the rings. Occasionally, a rattlesnake will lose it’s rattles. When this occurs, the difficulty of identification increases.

Rattlesnakes are ectothermic vertebrates (cold-blooded animals), meaning they lack an appropriate physiological mechanism for maintaining body temperature. All cold-blooded animals are at the mercy of their environment. Air and ground temperatures dramatically affect the environment of reptiles. This condition directly affects their daily rhythm of activity and their habitat.

There are six species of rattlesnakes in our area, including the Western Diamond Back (Crotalus atrox), Mohave (Crotalus scutulatus), Arizona Black (Crotalus vidiris), Black-Tailed (Crotalus molossos), Sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes), and the Tiger (Crotalus tigris). These animals have a very highly developed mechanism of injecting venom, therefore making them very successful predators. A rattlesnake’s diet is composed mostly of small rodents.

Reptiles, including rattlesnakes, like cool shady spots during the spring, summer and fall months. During the winter months rattlesnakes generally go underground and hibernate. They usually choose caves or old mine tunnels. Occasionally dens of rattlesnakes have been accidentally uncovered by construction equipment and hundreds of rattlesnakes are found at one time.

Rattlesnakes have been known to come out of hibernation if temperatures warm to 78 degrees Fahrenheit. The functioning temperature for a rattlesnake is 72 to 78 degrees and it’s effective temperature is 82 to 96 degrees. The effective temperature is the temperature at which the snake moves about and hunts for prey. Direct exposure to heat or sunlight will kill a rattlesnake in about 10 to 15 minutes.

You might say rattlesnake season in the lower Sonoran Desert is anytime temperatures rise above 72 degrees. Rattlesnakes are most commonly sighted from the first of April until about the middle of October. These animals are primarily nocturnal and prefer the hours after sundown and before sunrise. Most rattlesnake victims are bitten ½ hour before sundown and up to two hours after sundown. It is estimated that 72% of all bites occur during this period.

There are some interesting facts about rattlesnakes. The oldest known rattlesnake in captivity, a Western Diamond Back, was age 30 years and 7 months. The largest rattlesnake officially recorded was an Eastern Diamond Back (Crotalus adamatus) at 7 feet 4 inches long. The largest Western Diamondback was measured live at 6 feet 8 inches. There have been many wild claims about ten to fifteen-foot rattlesnakes, but usually these are snakes were measured after death and their skin had been stretched. The average distance a rattlesnake can strike and effectively inject venom is one-third of its body length.

Some 80% of all rattlesnake bites are the result of carelessness or the handling of rattlesnakes by older juveniles or young adults. It is now estimated some 20% of rattlesnake bites are accidental or legitimate. About 15% of rattlesnake bites are dry socket bites, meaning no venom was injected into the victim.

There are several signs and symptoms of envenomization. First, there will be fang marks. These fang marks can be singular, dual or even a scratch. Fang marks are generally a very small puncture wound and a burning sensation usually follows the injection of venom by the reptile.

A metallic or rubbery taste in the mouth often follows a bite, but not always. The tingling of the tongue or numbness can also occur. If a rattlesnake has injected venom into its victim, local swelling will occur within ten minutes. The amount of envenomization is generally indicated by the severity of edema or swelling at fang puncture site. Nausea and weakness is often associated with snakebite.

Black or blue discoloration will generally appear near the site of envenomization after three to six hours. Every snake bite victim should be treated for shock, which is a greater threat to the victim of snakebite than the venom.

Call 911 immediately; snakebite is a medical emergency. If medical help is several hours away the following treatment is recommended. Calm and reassure the victim, decrease the movement of the limb. Identify the snake if it is possible without further risk of another bite. It is not recommended to use a constricting band or tourniquet unless you are a medical professional. Many snakebite victims have come into emergency rooms with a constricting band, such as shoelace, completely obliterated by edema or swelling. It is extremely important to move the victim to a medical facility without delay.

Of course, it is best to prevent rattlesnake bite. When walking in the desert or in any area known for reptile habitation, always look where you step, or place your foot, or feet (caution should always be used at night, late evening, and early morning). Always look where you are placing your hands or fingers. Use extreme caution before placing your hands where you can not see what you are touching. Always look before sitting down, especially around or near boulders or brush. Think before defecating or urinating in the outdoors.

I have observed a variety of bites during the past fifty years that resulted from total lack of common sense. Small children must be closely supervised at all times in areas of possible snake infestation or inhabitation.

If you and your family observe these basic rules you should be safe from snakebite. As urbanization continues at the desert edge in Arizona the threat if snakebite is always a reality.

I would like to thank Jude McNally and his staff, Arizona Poison Control Center, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, and Dr. Findlay E. Russell and his enormously valuable resource "Snake Venom Poisoning" printed by Scholium International, Inc. Great Neck, New York 11021 Note: This book is a physician’s desk reference for snake venom poisoning.

For information call Arizona Poison Control System 1-800-362-0101. For snake removal in Apache Junction call Apache Junction Fire District at 982-4440.

Editor’s note: Tom Kollenborn directed the Snake Alert program for the Apache Junction Unified School District for seventeen years. He attended workshops and worked closely with the University of Arizona Poison Control Center and Medical Center.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)